Multiple security firms recently identified cryptocurrency mining service Coinhive as the top malicious threat to Web users, thanks to the tendency for Coinhive’s computer code to be used on hacked Web sites to steal the processing power of its visitors’ devices. This post looks at how Coinhive vaulted to the top of the threat list less than a year after its debut, and explores clues about the possible identities of the individuals behind the service.

Coinhive is a cryptocurrency mining service that relies on a small chunk of computer code designed to be installed on Web sites. The code uses some or all of the computing power of any browser that visits the site in question, enlisting the machine in a bid to mine bits of the Monero cryptocurrency.

Monero differs from Bitcoin in that its transactions are virtually untraceble, and there is no way for an outsider to track Monero transactions between two parties. Naturally, this quality makes Monero an especially appealing choice for cybercriminals.

Coinhive released its mining code last summer, pitching it as a way for Web site owners to earn an income without running intrusive or annoying advertisements. But since then, Coinhive’s code has emerged as the top malware threat tracked by multiple security firms. That’s because much of the time the code is installed on hacked Web sites — without the owner’s knowledge or permission.

Much like a malware infection by a malicious bot or Trojan, Coinhive’s code frequently locks up a user’s browser and drains the device’s battery as it continues to mine Monero for as long a visitor is browsing the site.

According to publicwww.com, a service that indexes the source code of Web sites, there are nearly 32,000 Web sites currently running Coinhive’s JavaScript miner code. It’s impossible to say how many of those sites have installed the code intentionally, but in recent months hackers have secretly stitched it into some extremely high-profile Web sites, including sites for such companies as The Los Angeles Times, mobile device maker Blackberry, Politifact, and Showtime.

And it’s turning up in some unexpected places: In December, Coinhive code was found embedded in all Web pages served by a WiFi hotspot at a Starbucks in Buenos Aires. For roughly a week in January, Coinhive was found hidden inside of YouTube advertisements (via Google’s DoubleClick platform) in select countries, including Japan, France, Taiwan, Italy and Spain. In February, Coinhive was found on “Browsealoud,” a service provided by Texthelp that reads web pages out loud for the visually impaired. The service is widely used on many UK government websites, in addition to a few US and Canadian government sites.

What does Coinhive get out of all this? Coinhive keeps 30 percent of whatever amount of Monero cryptocurrency that is mined using its code, whether or not a Web site has given consent to run it. The code is tied to a special cryptographic key that identifies which user account is to receive the other 70 percent.

Coinhive does accept abuse complaints, but it generally refuses to respond to any complaints that do not come from a hacked Web site’s owner (it mostly ignores abuse complaints lodged by third parties). What’s more, when Coinhive does respond to abuse complaints, it does so by invalidating the key tied to the abuse.

But according to Troy Mursch, a security expert who spends much of his time tracking Coinhive and other instances of “cryptojacking,” killing the key doesn’t do anything to stop Coinhive’s code from continuing to mine Monero on a hacked site. Once a key is invalidated, Mursch said, Coinhive keeps 100 percent of the cryptocurrency mined by sites tied to that account from then on.

Mursch said Coinhive appears to have zero incentive to police the widespread abuse that is leveraging its platform.

“When they ‘terminate’ a key, it just terminates the user on that platform, it doesn’t stop the malicious JavaScript from running, and it just means that particular Coinhive user doesn’t get paid anymore,” Mursch said. “The code keeps running, and Coinhive gets all of it. Maybe they can’t do anything about it, or maybe they don’t want to. But as long as the code is still on the hacked site, it’s still making them money.”

Reached for comment about this apparent conflict of interest, Coinhive replied with a highly technical response, claiming the organization is working on a fix to correct that conflict.

“We have developed Coinhive under the assumption that site keys are immutable,” Coinhive wrote in an email to KrebsOnSecurity. “This is evident by the fact that a site key can not be deleted by a user. This assumption greatly simplified our initial development. We can cache site keys on our WebSocket servers instead of reloading them from the database for every new client. We’re working on a mechanism [to] propagate the invalidation of a key to our WebSocket servers.”

AUTHEDMINE

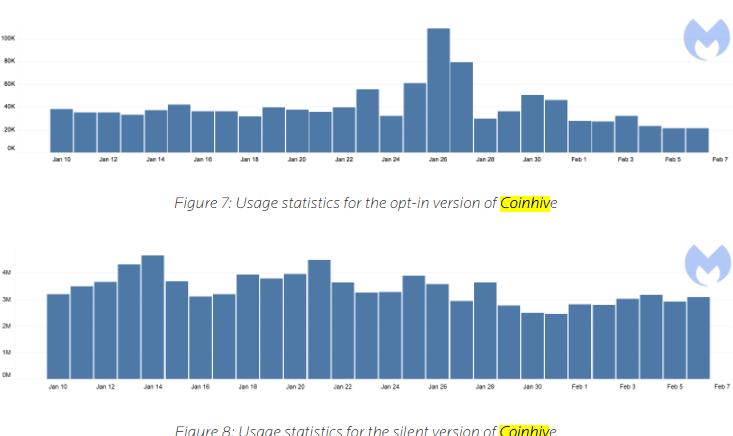

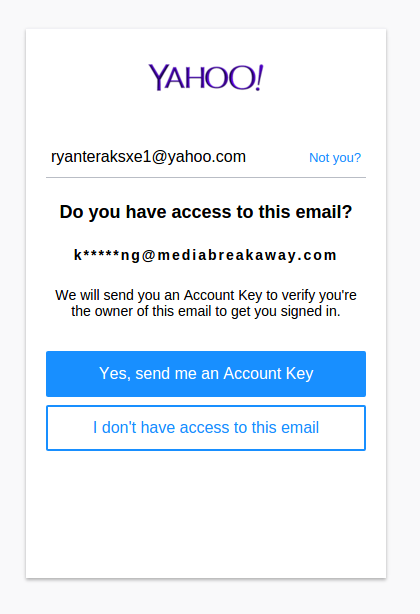

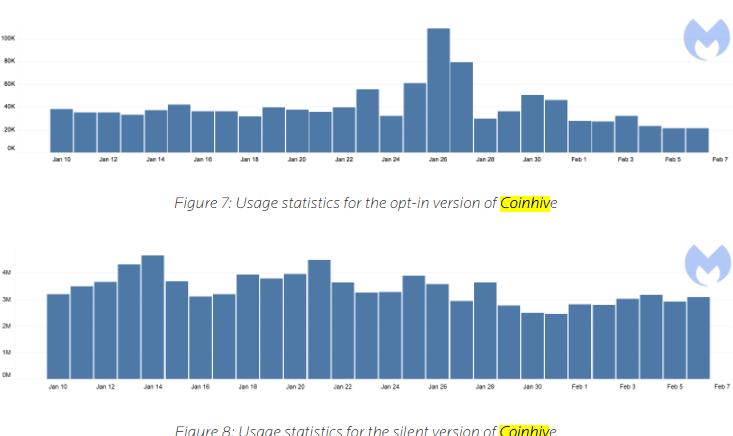

Coinhive has responded to such criticism by releasing a version of their code called “AuthedMine,” which is designed to seek a Web site visitor’s consent before running the Monero mining scripts. Coinhive maintains that approximately 35 percent of the Monero cryptocurrency mining activity that uses its platform comes from sites using AuthedMine.

But according to a report published in February by security firm Malwarebytes, the AuthedMine code is “barely used” compared to the use of Coinhive’s mining code that does not seek permission from Web site visitors. Malwarebytes’ telemetry data (drawn from antivirus alerts when users browse to a site running Coinhive’s code) determined that AuthedMine is used in a little more than one percent of all cases that involve Coinhive’s mining code.

Image: Malwarebytes. The statistic above refer to the number of times per day between Jan. 10 and Feb. 7 that Malwarebytes blocked connections to AuthedMine and Coinhive, respectively.

Asked to comment on the Malwarebytes findings, Coinhive replied that if relatively few people are using AuthedMine it might be because anti-malware companies like Malwarebytes have made it unprofitable for people to do so.

“They identify our opt-in version as a threat and block it,” Coinhive said. “Why would anyone use AuthedMine if it’s blocked just as our original implementation? We don’t think there’s any way that we could have launched Coinhive and not get it blacklisted by Antiviruses. If antiviruses say ‘mining is bad,’ then mining is bad.”

Similarly, data from the aforementioned source code tracking site publicwww.com shows that some 32,000 sites are running the original Coinhive mining script, while the site lists just under 1,200 sites running AuthedMine.

WHO IS COINHIVE?

[Author’s’ note: Ordinarily, I prefer to link to sources of information cited in stories, such as those on Coinhive’s own site and other entities mentioned throughout the rest of this piece. However, because many of these links either go to sites that actively mine with Coinhive or that include decidedly not-safe-for-work content, I have included screenshots instead of links in these cases].

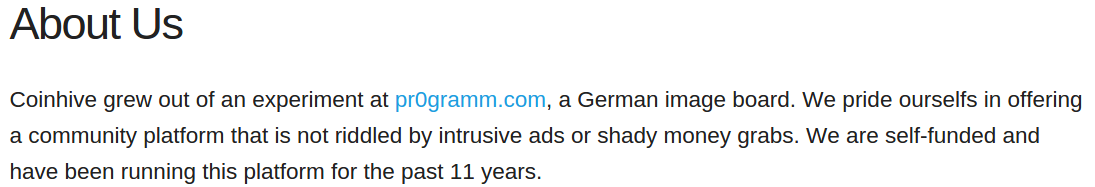

According to a since-deleted statement on the original version of Coinhive’s Web site — coin-hive[dot]com — Coinhive was born out of an experiment on the German-language image hosting and discussion forum pr0gramm[dot]com.

A now-deleted “About us” statement on the original coin-hive[dot]com Web site. This snapshop was taken on Sept. 15, 2017. Image courtesy archive.org.

Indeed, multiple discussion threads on pr0gramm[dot]com show that Coinhive’s code first surfaced there in the third week of July 2017. At the time, the experiment was dubbed “

pr0miner,” and those threads indicate that the core programmer responsible for pr0miner used the nickname “

int13h” on pr0gramm. In a message to this author, Coinhive confirmed that “most of the work back then was done by int13h, who is still on our team.”

I asked Coinhive for clarity on the disappearance of the above statement from its site concerning its affiliation with pr0gramm. Coinhive replied that it had been a convenient fiction:

“The owners of pr0gramm are good friends and we’ve helped them with their infrastructure and various projects in the past. They let us use pr0gramm as a testbed for the miner and also allowed us to use their name to get some more credibility. Launching a new platform is difficult if you don’t have a track record. As we later gained some publicity, this statement was no longer needed.”

Asked for clarification about the “platform” referred to in its statement (“We are self-funded and have been running this platform for the past 11 years”) Coinhive replied, “Sorry for not making it clearer: ‘this platform’ is indeed pr0gramm.”

After receiving this response, it occurred to me that someone might be able to find out who’s running Coinhive by determining the identities of the pr0gramm forum administrators. I reasoned that if they were not one and the same, the pr0gramm admins almost certainly would know the identities of the folks behind Coinhive.

WHO IS PR0GRAMM?

So I set about trying to figure out who’s running pr0gramm. It wasn’t easy, but in the end all of the information needed to determine that was freely available online.

Let me be crystal clear on this point: All of the data I gathered (and presented in the detailed ‘mind map’ below) was derived from either public Web site WHOIS domain name registration records or from information posted to various social media networks by the pr0gramm administrators themselves. In other words, there is nothing in this research that was not put online by the pr0gramm administrators themselves.

I began with the pr0gramm domain itself which, like many other domains tied to this research, was originally registered to an individual named Dr. Matthias Moench. Mr. Moench is only tangentially connected to this research, so I will dispense with a discussion of him for now except to say that he is a convicted spammer and murderer, and that the last subsection of this story explains who Moench is and why he may be connected to so many of these domains. His is a fascinating and terrifying story.

Through many weeks of research, I learned that pr0gramm was originally tied to a network of adult Web sites linked to two companies that were both incorporated more than a decade ago in Las Vegas, Nevada: Eroxell Limited, and Dustweb Inc. Both of these companies stated they were involved in online advertising of some form or another.

Both Eroxell and Dustweb, as well as several related pr0gramm Web sites (e.g., pr0mining[dot]com, pr0mart[dot]de, pr0shop[dot]com) are connected to a German man named Reinhard Fuerstberger, whose domain registration records include the email address “admin@pr0gramm[dot]com”. Eroxell/Dustweb also each are connected to a company incorporated in Spain called Suntainment SL, of which Fuerstberger is the apparent owner.

As stated on pr0gramm’s own site, the forum began in 2007 as a German language message board that originated from an automated bot that would index and display images posted to certain online chat channels associated with the wildly popular video first-person shooter game Quake.

As the forum’s user base grew, so did the diversity of the site’s cache of images, and pr0gramm began offering paid so-called “pr0mium” accounts that allowed users to view all of the forum’s not-safe-for-work images and to comment on the discussion board. When pr0gramm last July first launched pr0miner (the precursor to what is now Coinhive), it invited pr0gramm members to try the code on their own sites, offering any who did so to claim their reward in the form of pr0mium points.

DEIMOS AND PHOBOS

Pr0gramm was launched in late 2007 by a Quake enthusiast from Germany named Dominic Szablewski, a computer expert better known to most on pr0gramm by his screen name “cha0s.”

At the time of pr0gramm’s inception, Szbalewski ran a Quake discussion board called chaosquake[dot]de, and a personal blog — phoboslab[dot]org. I was able to determine this by tracing a variety of connections, but most importantly because phoboslab and pr0gramm both once shared the same Google Analytics tracking code (UA-571256).

Reached via email, Szablewski said he did not wish to comment for this story beyond stating that he sold pr0gramm a few years ago to another, unnamed individual.

Multiple longtime pr0gramm members have remarked that since cha0s departed as administrator, the forum has become overrun by individuals with populist far-right political leanings. Mr. Fuerstberger describes himself on various social media sites as a “politically incorrect, Bavarian separatist” [Wiki link added]. What’s more, there are countless posts on pr0gramm that are particularly hateful and denigrating to specific ethnic or religious groups.

Responding to questions via email, Fuerstberger said he had no idea pr0gramm was used to launch Coinhive.

“I can assure you that I heard about Coinhive for the first time in my life earlier this week,” he said. “I can assure you that the company Suntainment has nothing to do with it. I do not even have anything to do with Pr0gram. That’s what my partner does. When I found out now what was abusing my company, I was shocked.”

Below is a “mind map” I assembled to keep track of the connections between and among the various names, emails and Web sites mentioned in this research.

A “mind map” I put together to keep track of and organize my research on pr0gramm and Coinhive. This map was created with Mindnode Pro for Mac. Click to enlarge.

GAMB

I was able to learn the identity of Fuerstberger’s partner — the current pr0gramm administrator, who goes by the nickname “Gamb” — by following the WHOIS data from sites registered to the U.S.-based company tied to pr0gramm (Eroxell Ltd).

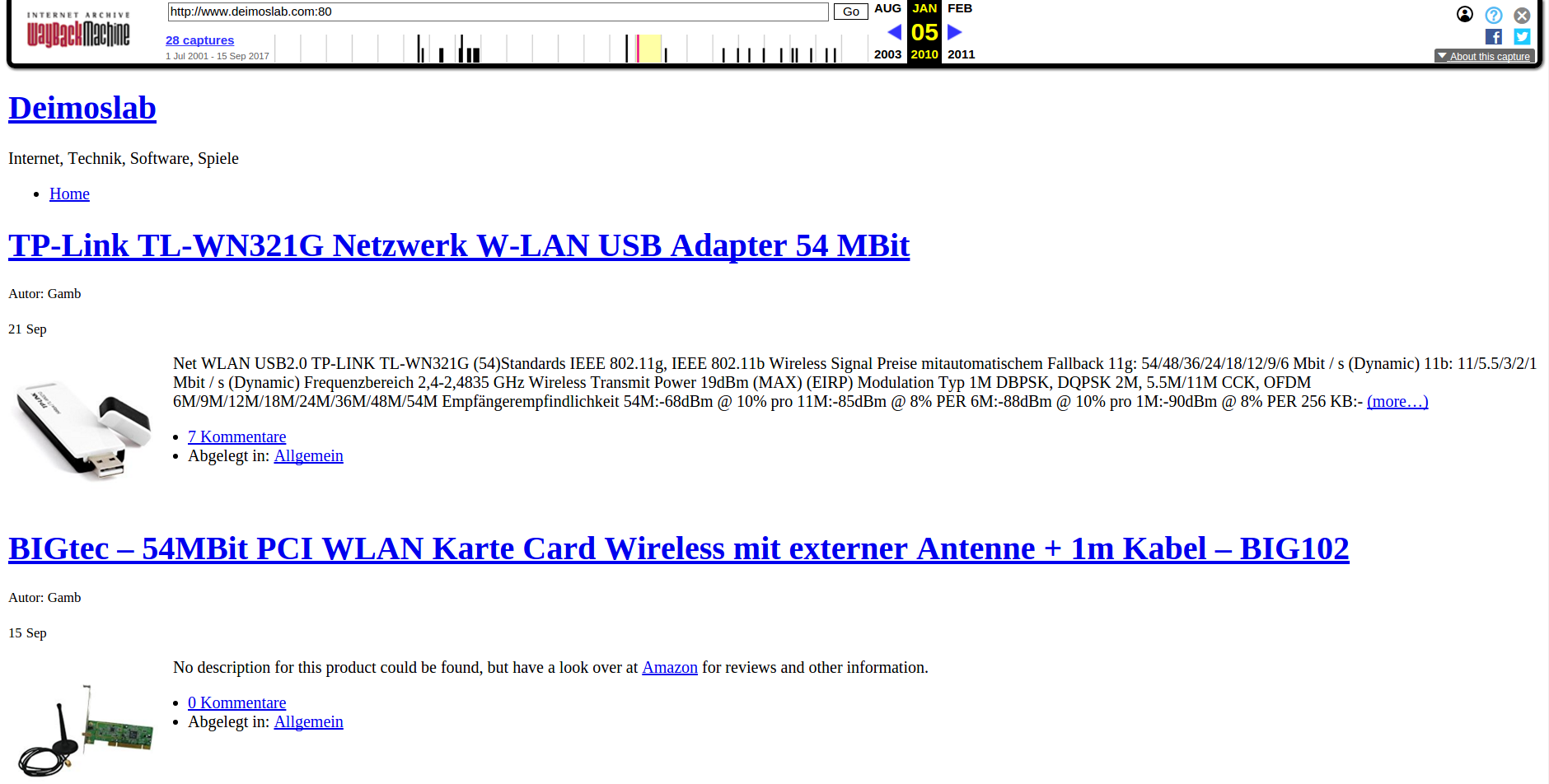

Among the many domains registered to Eroxell was deimoslab[dot]com, which at one point was a site that sold electronics. As can be seen below in a copy of the site from 2010 (thanks to archive.org), the proprietor of deimoslab used the same Gamb nickname.

Deimos and Phobos are the names of the two moons of the planet Mars. They also refer to the names of the fourth and fifth level in the computer game “Doom.” In addition, they are the names of two spaceships that feature prominently in the game Quake II.

A screenshot of Deimoslab.com from 2010 (courtesy of archive.org) shows the user “Gamb” was responsible for the site.

A passive DNS lookup on an Internet address long used by pr0gramm[dot]com shows that deimoslab[dot]com once shared the server with several other domains, including phpeditor[dot]de. According to a historic WHOIS lookup on phpeditor[dot]de, the domain was originally registered by an Andre Krumb from Gross-Gerau, Germany.

When I discovered this connection, I still couldn’t see anything tying Krumb to “Gamb,” the nickname of the current administrator of pr0gramm. That is, until I began searching the Web for online forum accounts leveraging usernames that included the nickname “Gamb.”

One such site is ameisenforum[dot]de, a discussion forum for people interested in creating and raising ant farms. I didn’t know what to make of this initially and so at first disregarded it. That is, until I discovered that the email address used to register phpeditor[dot]de also was used to register a rather unusual domain: antsonline[dot]de.

In a series of email exchanges with KrebsOnSecurity, Krumb acknowledged that he was the administrator of pr0gramm (as well as chief technology officer at the aforementioned Suntainment SL), but insisted that neither he nor pr0gramm was involved in Coinhive.

Krumb repeatedly told me something I still have trouble believing: That Coinhive was the work of just one individual — int13h, the pr0gramm user credited by Coinhive with creating its mining code.

“Coinhive is not affiliated with Suntainment or Suntainment’s permanent employees in any way,” Krumb said in an email, declining to share any information about int13h. “Also it’s not a group of people you are looking for, it’s just one guy who sometimes worked for Suntainment as a freelancer.”

COINHIVE CHANGES ITS STORY, WEB SITE

Very soon after I began receiving email replies from Mr. Fuerstberger and Mr. Krumb, I started getting emails from Coinhive again.

“Some people involved with pr0gramm have contacted us, saying they’re being extorted by you,” Coinhive wrote. “They want to run pr0gramm anonymously because admins and moderators had a history of being harassed by some trolls. I’m sure you can relate to that. You have them on edge, which of course is exactly where you want them. While we must applaud your efficiency for finding information, your tactics for doing so are questionable in our opinion.”

Coinhive was rather dramatically referring to my communications with Krumb, in which I stated that I was seeking more information about int13h and anyone else affiliated with Coinhive.

“We want to make it very clear again that Coinhive in its current form has nothing to do with pr0gramm or its owners,” Coinhive said. “We tested a ‘toy implementation’ of the miner on pr0gramm, because they had a community open for these kind of things. That’s it.”

When asked about their earlier statement to this author — that the people behind Coinhive claimed pr0gramm as “their platform of 11 years” (which, incidentally, is exactly how long pr0gramm has been online) — Coinhive reiterated its revised statement: That this had been a convenient fabrication, and that the two were completely separate organizations.

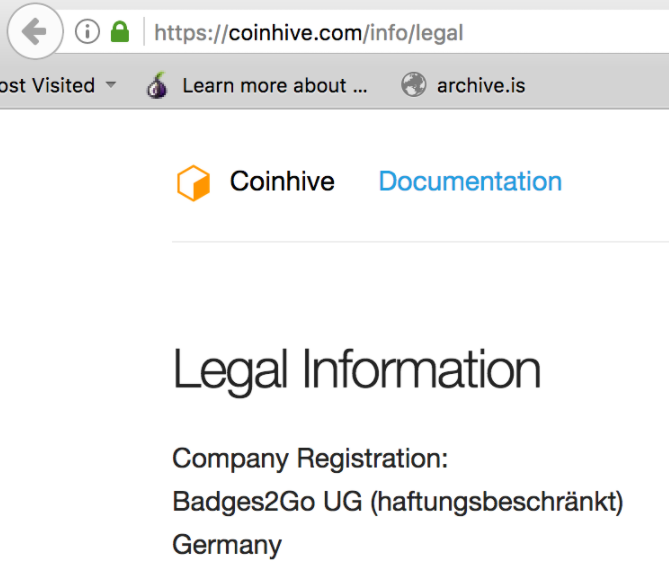

On March 22, the Coinhive folks sent me a follow-up email, saying that in response to my inquiries they consulted their legal team and decided to add some contact information to their Web site.

“Legal information” that Coinhive added to its Web site on March 22 in response to inquiries from this reporter.

That addition, which can be viewed at coinhive[dot]com/legal, lists a company in Kaiserlautern, Germany called Badges2Go UG. Business records show Badges2Go is a limited liability company established in April 2017 and headed by a Sylvia Klein from Frankfurt. Klein’s Linkedin profile states that she is the CEO of several organizations in Germany, including one called Blockchain Future.

“I founded Badges2Go as an incubator for promising web and mobile applications,” Klein said in a instant message chat with KrebsOnSecurity. “Coinhive is one of them. Right now we check the potential and fix the next steps to professionalize the service.”

THE BIZARRE SIDE STORY OF DR. MATTHIAS MOENCH

I have one final and disturbing anecdote to share about some of the Web site registration data in the mind map above. As mentioned earlier, readers can see that many of the domain names tied to the pr0gramm forum administrators were originally registered to an individual named “Dr. Matthias Moench.”

When I first began this research back in January 2018, I guessed that Mr. Moench was almost certainly a pseudonym used to throw off researchers. But the truth is Dr. Moench is indeed a real person — and a very scary individual at that.

According to a chilling 2014 article in the German daily newspaper Die Welt, Moench was the son of a wealthy entrepreneurial family in Germany who was convicted at age 19 of hiring a Turkish man to murder his parents a year earlier in 1988. Die Welt says the man Moench hired used a machete to hack to death Moench’s parents and the family poodle. Moench reportedly later explained his actions by saying he was upset that his parents bought him a used car for his 18th birthday instead of the Ferrari that he’d always wanted.

Matthias Moench in 1989. Image: Welt.de.

Moench was ultimately convicted and sentenced to nine years in a juvenile detention facility, but he would only serve five years of that sentence. Upon his release, Moench claimed he had found religion and wished to become a priest.

Somewhere along the way, however, Moench ditched the priest idea and decided to become a spammer instead. For years, he worked assiduously to pump out spam emails pimping erectile dysfunction medications, reportedly earning at least 21.5 million Euros from his various spamming activities.

Once again, Mr. Moench was arrested and put on trial. In 2015, he and several other co-defendants were convicted of fraud and drug-related offenses. Moench was sentenced to six years in prison. According to Lars-Marten Nagel, the author of the original Die Welt story on Moench’s murderous childhood, German prosecutors say Moench is expected to be released from prison later this year.

It may be tempting to connect the pr0gramm administrators with Mr. Moench, but it seems likely that there is little to no connection here. An incredibly detailed blog post from 2006 which sought to determine the identity of the Matthias Moench named as the original registrant of so many domains (they number in the tens of thousands) found that Moench himself stated on several Internet forums that his name and mailing addresses in Germany and the Czech Republic could be freely used or abused by any like-minded spammer or scammer who wished to hide his identity. Apparently, many people took him up on that offer.

from

https://krebsonsecurity.com/2018/03/who-and-what-is-coinhive/

The Microsoft updates affect all supported Windows operating systems, as well as all supported versions of Internet Explorer/Edge, Office, Sharepoint and Exchange Server.

The Microsoft updates affect all supported Windows operating systems, as well as all supported versions of Internet Explorer/Edge, Office, Sharepoint and Exchange Server. Microsoft says by default, Windows 10 receives updates automatically, “and for customers running previous versions, we recommend they

Microsoft says by default, Windows 10 receives updates automatically, “and for customers running previous versions, we recommend they