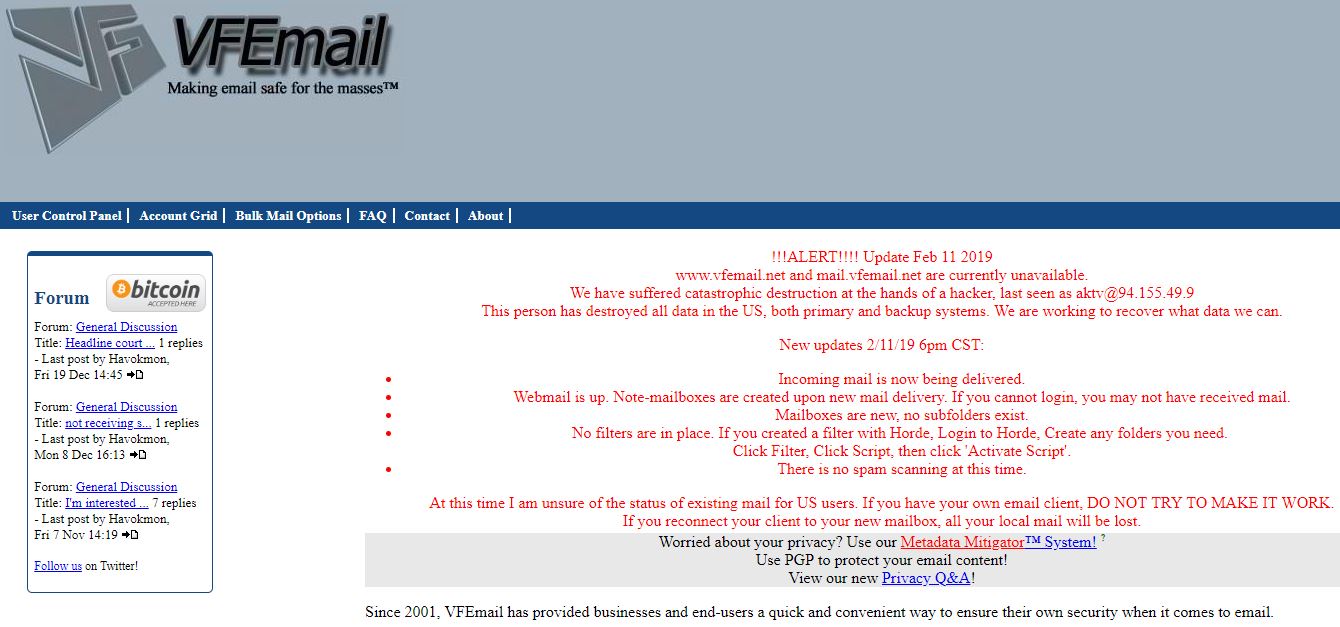

The U.S. government — along with a number of leading security companies — recently warned about a series of highly complex and widespread attacks that allowed suspected Iranian hackers to siphon huge volumes of email passwords and other sensitive data from multiple governments and private companies. But to date, the specifics of exactly how that attack went down and who was hit have remained shrouded in secrecy.

This post seeks to document the extent of those attacks, and traces the origins of this overwhelmingly successful cyber espionage campaign back to a cascading series of breaches at key Internet infrastructure providers.

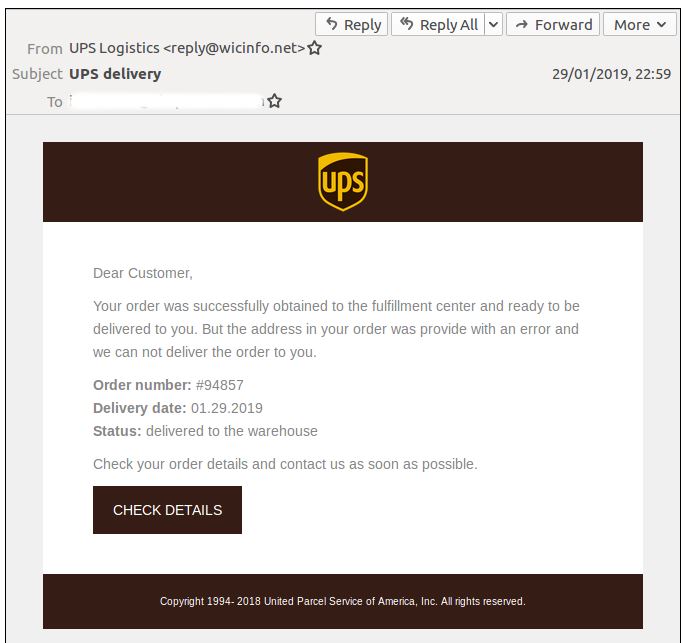

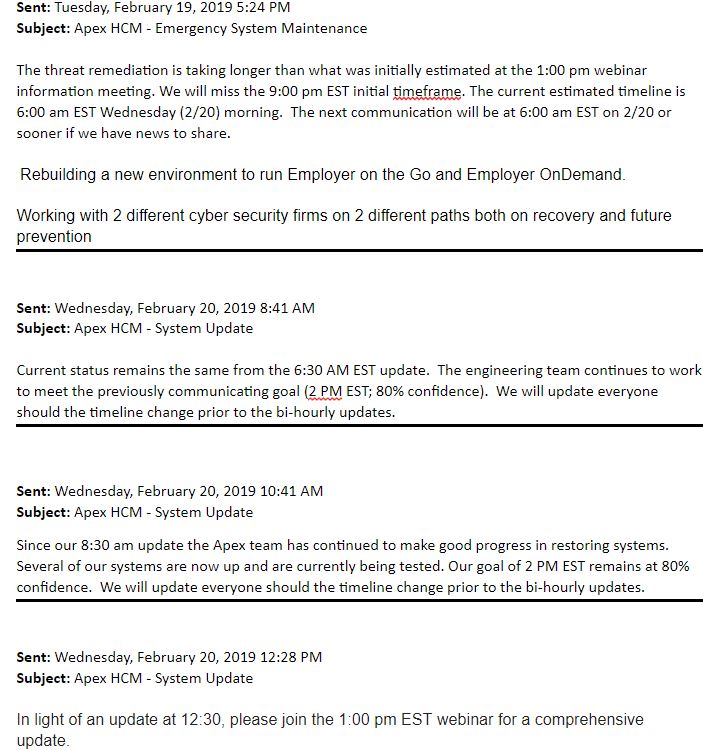

Before we delve into the extensive research that culminated in this post, it’s helpful to review the facts disclosed publicly so far. On Nov. 27, 2018, Cisco’s Talos research division published a write-up outlining the contours of a sophisticated cyber espionage campaign it dubbed “DNSpionage.”

The DNS part of that moniker refers to the global “Domain Name System,” which serves as a kind of phone book for the Internet by translating human-friendly Web site names (example.com) into numeric Internet address that are easier for computers to manage.

Talos said the perpetrators of DNSpionage were able to steal email and other login credentials from a number of government and private sector entities in Lebanon and the United Arab Emirates by hijacking the DNS servers for these targets, so that all email and virtual private networking (VPN) traffic was redirected to an Internet address controlled by the attackers.

Talos reported that these DNS hijacks also paved the way for the attackers to obtain SSL encryption certificates for the targeted domains (e.g. webmail.finance.gov.lb), which allowed them to decrypt the intercepted email and VPN credentials and view them in plain text.

On January 9, 2019, security vendor FireEye released its report, “Global DNS Hijacking Campaign: DNS Record Manipulation at Scale,” which went into far greater technical detail about the “how” of the espionage campaign, but contained few additional details about its victims.

Twelve days after the FireEye report, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security issued a rare emergency directive ordering all U.S. federal civilian agencies to secure the login credentials for their Internet domain records. As part of that mandate, DHS published a short list of domain names and Internet addresses that were used in the DNSpionage campaign, although those details did not go beyond what was previously released by either Cisco Talos or FireEye.

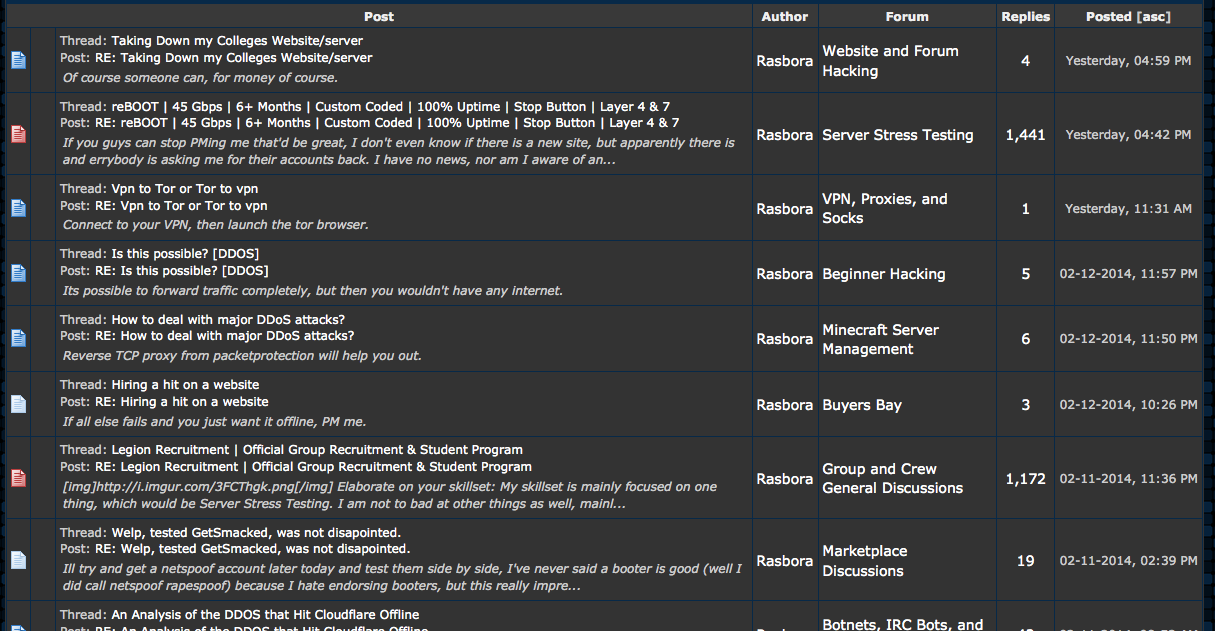

That changed on Jan. 25, 2019, when security firm CrowdStrike published a blog post listing virtually every Internet address known to be (ab)used by the espionage campaign to date. The remainder of this story is based on open-source research and interviews conducted by KrebsOnSecurity in an effort to shed more light on the true extent of this extraordinary — and ongoing — attack.

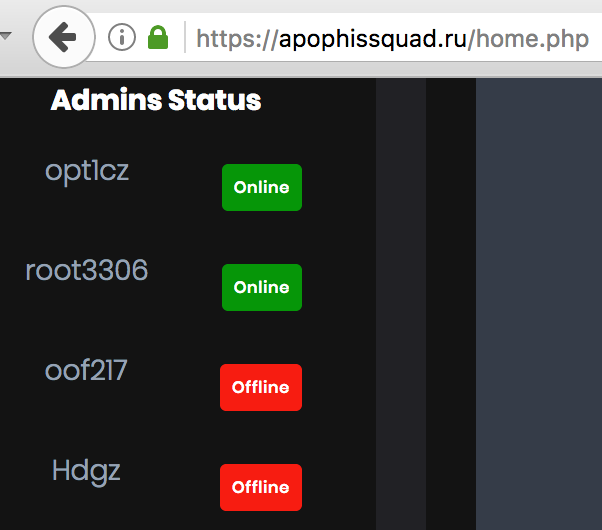

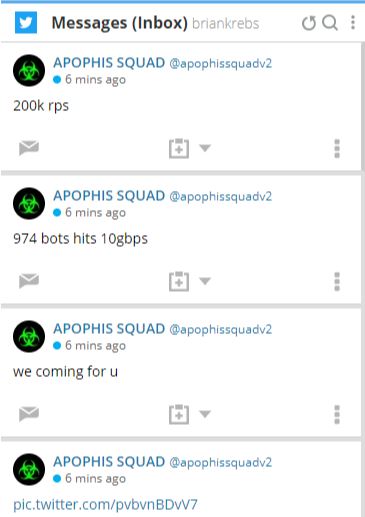

The “indicators of compromise” related to the DNSpionage campaign, as published by CrowdStrike.

PASSIVE DNS

I began my research by taking each of the Internet addresses laid out in the CrowdStrike report and running them through both Farsight Security and SecurityTrails, services that passively collect data about changes to DNS records tied to tens of millions of Web site domains around the world.

Working backwards from each Internet address, I was able to see that in the last few months of 2018 the hackers behind DNSpionage succeeded in compromising key components of DNS infrastructure for more than 50 Middle Eastern companies and government agencies, including targets in Albania, Cyprus, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

For example, the passive DNS data shows the attackers were able to hijack the DNS records for mail.gov.ae, which handles email for government offices of the United Arab Emirates. Here are just a few other interesting assets successfully compromised in this cyber espionage campaign:

-nsa.gov.iq: the National Security Advisory of Iraq

-webmail.mofa.gov.ae: email for the United Arab Emirates’ Ministry of Foreign Affairs

-shish.gov.al: the State Intelligence Service of Albania

-mail.mfa.gov.eg: mail server for Egypt’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs

-mod.gov.eg: Egyptian Ministry of Defense

-embassy.ly: Embassy of Libya

-owa.e-albania.al: the Outlook Web Access portal for the e-government portal of Albania

-mail.dgca.gov.kw: email server for Kuwait’s Civil Aviation Bureau

-gid.gov.jo: Jordan’s General Intelligence Directorate

-adpvpn.adpolice.gov.ae: VPN service for the Abu Dhabi Police

-mail.asp.gov.al: email for Albanian State Police

-owa.gov.cy: Microsoft Outlook Web Access for Government of Cyprus

-webmail.finance.gov.lb: email for Lebanon Ministry of Finance

-mail.petroleum.gov.eg: Egyptian Ministry of Petroleum

-mail.cyta.com.cy: Cyta telecommunications and Internet provider, Cyprus

-mail.mea.com.lb: email access for Middle East Airlines

The passive DNS data provided by Farsight and SecurityTrails also offered clues about when each of these domains was hijacked. In most cases, the attackers appear to have changed the DNS records for these domains (we’ll get to the “how” in a moment) so that the domains pointed to servers in Europe that they controlled.

Shortly after the DNS records for these TLDs were hijacked — sometimes weeks, sometimes just days or hours — the attackers were able to obtain SSL certificates for those domains from SSL providers Comodo and/or Let’s Encrypt. The preparation for several of these attacks can be seen at cert.sh, which provides a searchable database of all new SSL certificate creations.

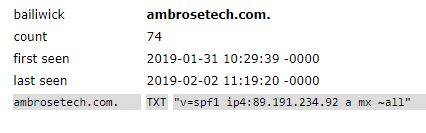

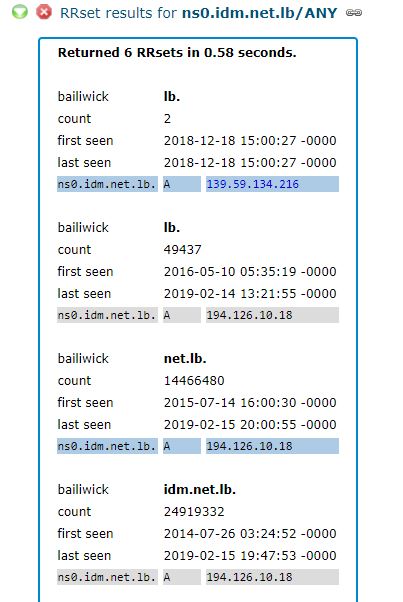

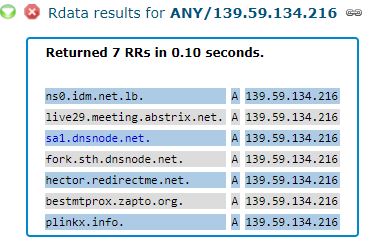

Let’s take a closer look at one example. The CrowdStrike report references the Internet address 139.59.134[.]216 (see above), which according to Farsight was home to just seven different domains over the years. Two of those domains only appeared at that Internet address in December 2018, including domains in Lebanon and — curiously — Sweden.

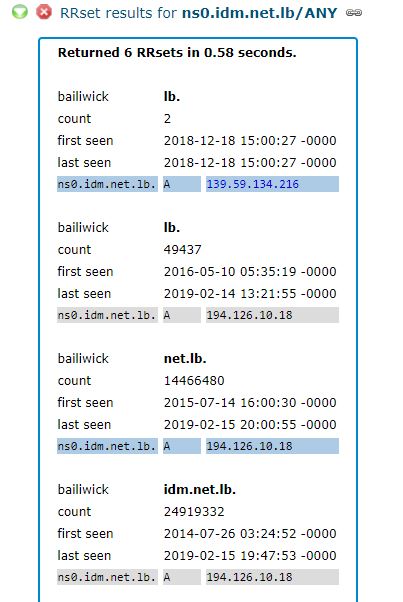

The first domain was “ns0.idm.net.lb,” which is a server for the Lebanese Internet service provider IDM. From early 2014 until December 2018, ns0.idm.net.lb pointed to 194.126.10[.]18, which appropriately enough is an Internet address based in Lebanon. But as we can see in the screenshot from Farsight’s data below, on Dec. 18, 2018, the DNS records for this ISP were changed to point Internet traffic destined for IDM to a hosting provider in Germany (the 139.59.134[.]216 address).

Source: Farsight Security

Notice what else is listed along with IDM’s domain at 139.59.134[.]216, according to Farsight:

The DNS records for the domains sa1.dnsnode.net and fork.sth.dnsnode.net also were changed from their rightful home in Sweden to the German hosting provider controlled by the attackers in December. These domains are owned by Netnod Internet Exchange, a major global DNS provider based in Sweden. Netnod also operates one of the 13 “root” name servers, a critical resource that forms the very foundation of the global DNS system.

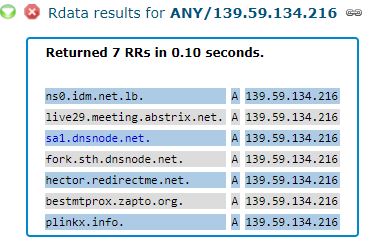

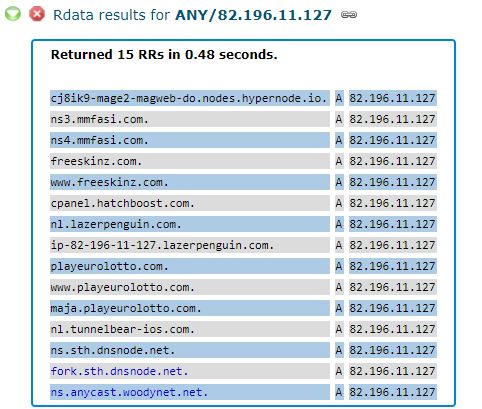

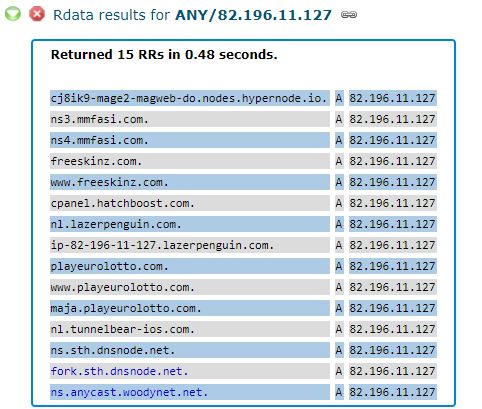

We’ll come back to Netnod in a moment. But first let’s look at another Internet address referenced in the CrowdStrike report as part of the infrastructure abused by the DNSpionage hackers: 82.196.11[.]127. This address in The Netherlands also is home to the domain mmfasi[.]com, which Crowdstrike says was one of the attacker’s domains that was used as a DNS server for some of the hijacked infrastructure.

As we can see in the screenshot above, 82.196.11[.]127 was temporarily home to another pair of Netnod DNS servers, as well as the server “ns.anycast.woodynet.net.” That domain is derived from the nickname of Bill Woodcock, who serves as executive director of Packet Clearing House (PCH).

PCH is a nonprofit entity based in northern California that also manages significant amounts of the world’s DNS infrastructure, particularly the DNS for more than 500 top-level domains and a number of the Middle East top-level domains targeted by DNSpionage.

TARGETING THE REGISTRARS

Contacted on Feb. 14 by KrebsOnSecurity, Netnod CEO Lars Michael Jogbäck confirmed that parts of Netnod’s DNS infrastructure were hijacked in late December 2018 and early January 2019 after the attackers gained access to accounts at Netnod’s domain name registrar.

Jogbäck pointed to a statement the company published on its Web site on Feb. 5, which says Netnod learned of its role in the attack on January 2 and has been in contact with all relevant parties and customers throughout this process.

“As a participant in an international security co-operation, Netnod became aware on 2 January 2019 that we had been caught up in this wave and that we had experienced a MITM (man-in-the-middle) attack,” the statement reads. “Netnod was not the ultimate goal of the attack. The goal is considered to have been the capture of login details for Internet services in countries outside of Sweden.”

In an interview with this author on Feb. 15, PCH’s Woodcock acknowledged that portions of his organization’s DNS infrastructure were compromised after the DNSpionage hackers abused unauthorized access to its domain name registrar.

As it happens, the registrar records for both pch.net and dnsnode.net point to the same sources: Key-Systems GmbH, a domain registrar based in Germany; and Frobbit.se, a company in Sweden. Frobbit is a reseller of Key Systems, and the two companies share some of the same online resources.

Woodcock said domain records for the targeted Middle East TLDs it managed were altered after the DNSpionage hackers phished credentials that Key-Systems uses to make domain changes for their clients.

Specifically, he said, the hackers phished credentials that PCH’s registrar used to send signaling messages known as the Extensible Provisioning Protocol (EPP). EPP is a little-known interface that serves as a kind of back-end for the global DNS system, allowing domain registrars to notify the regional registries (like Verisign) about changes to domain records, including new domain registrations, modifications, and transfers.

“At the beginning of January, Key-Systems said they believed that their EPP interface had been abused by someone who had stolen valid credentials,” Woodcock said.

Key-Systems declined to comment for this story, beyond saying it does not discuss details of its reseller clients’ businesses.

Netnod’s written statement on the attack referred further inquiries to the company’s security director Patrik Fältström, who also is co-owner of Frobbit.se.

In an email to KrebsOnSecurity, Fältström said unauthorized EPP instructions were sent to various registries by the DNSpionage attackers from both Frobbit and Key Systems.

“The attack was from my perspective clearly an early version of a serious EPP attack,” he wrote. “That is, the goal was to get the right EPP commands sent to the registries. I am extremely nervous personally over extrapolations towards the future. Should registries allow any EPP command to come from the registrars? We will always have some weak registrars, right?”

DNSSEC

One of the more interesting aspects of these attacks is that both Netnod and PCH are vocal proponents and adopters of DNSSEC (a.k.a. “DNS Security Extensions”), which is a technology designed to defeat the very type of attack that the DNSpionage hackers were able to execute.

Image: APNIC

DNSSEC protects applications from using forged or manipulated DNS data, by requiring that all DNS queries for a given domain or set of domains be digitally signed. In DNSSEC, if a name server determines that the address record for a given domain has not been modified in transit, it resolves the domain and lets the user visit the site. If, however, that record has been modified in some way or doesn’t match the domain requested, the name server blocks the user from reaching the fraudulent address.

While DNSSEC can be an effective tool for mitigating attacks such as those launched by DNSpionage, only about 20 percent of the world’s major networks and Web sites have enabled it, according to measurements gathered by APNIC, the regional Internet address registry for the Asia-Pacific region.

Jogbäck said Netnod’s infrastructure suffered three separate attacks from the DNSpionage attackers. The first two occurred in a two-week window between Dec. 14, 2018 and Jan. 2, 2019, and targeted company servers that were not protected by DNSSEC.

However, he said the third attack between Dec. 29 and Jan. 2 targeted Netnod infrastructure that was protected by DNSSEC and serving its own internal email network. Yet, because the attackers already had access to its registrar’s systems, they were able to briefly disable that safeguard — or at least long enough to obtain SSL certificates for two of Netnod’s email servers.

Jogbäck told KrebsOnSecurity that once the attackers had those certificates, they re-enabled DNSSEC for the company’s targeted servers while apparently preparing to launch the second stage of the attack — diverting traffic flowing through its mail servers to machines the attackers controlled. But Jogbäck said that for whatever reason, the attackers neglected to use their unauthorized access to its registrar to disable DNSSEC before later attempting to siphon Internet traffic.

“Luckily for us, they forgot to remove that when they launched their man-in-the-middle attack,” he said. “If they had been more skilled they would have removed DNSSEC on the domain, which they could have done.”

Woodcock says PCH validates DNSSEC on all of its infrastructure, but that not all of the company’s customers — particularly some of the countries in the Middle East targeted by DNSpionage — had configured their systems to fully implement the technology.

Woodcock said PCH’s infrastructure was targeted by DNSpionage attackers in four distinct attacks between December 13, 2018 and January 2, 2019. With each attack, the hackers would turn on their password-slurping tools for roughly one hour, and then switch them off before returning the network to its original state after each run.

The attackers didn’t need to enable their surveillance dragnet longer than an hour each time because most modern smartphones are configured to continuously pull new email for any accounts the user may have set up on his device. Thus, the attackers were able to hoover up a great many email credentials with each brief hijack.

On Jan. 2, 2019 — the same day the DNSpionage hackers went after Netnod’s internal email system — they also targeted PCH directly, obtaining SSL certificates from Comodo for two PCH domains that handle internal email for the company.

Woodcock said PCH’s reliance on DNSSEC almost completely blocked that attack, but that it managed to snare email credentials for two employees who were traveling at the time. Those employees’ mobile devices were downloading company email via hotel wireless networks that — as a prerequisite for using the wireless service — forced their devices to use the hotel’s DNS servers, not PCH’s DNNSEC-enabled systems.

“The two people who did get popped, both were traveling and were on their iPhones, and they had to traverse through captive portals during the hijack period,” Woodcock said. “They had to switch off our name servers to use the captive portal, and during that time the mail clients on their phones checked for new email. Aside from that, DNSSEC saved us from being really, thoroughly owned.”

Because PCH had protected its domains with DNSSEC, the practical effect of the hijack against its mail infrastructure was that for roughly an hour nobody but the two remote employees received any email.

“For essentially all of our users, what it looked like was the mail server just wasn’t available for a short period,” Woodcock said. “It didn’t resolve for a while if they happened to be checking their phone or whatever, and each person thought well that’s funny, I’ll check it back in a while. And by the time they checked again it was working fine. A bunch of our staff noticed a brief outage in our email service, but nobody thought enough of it to discuss it with anyone else or open a ticket.”

But the DNSpionage hackers were not deterred. In a letter to its customers sent earlier this month, PCH said a forensic investigation determined that on Jan. 24 a computer which holds its Web site user database had been compromised. The user data stored in the database included customer usernames, bcrypt password hashes, emails, addresses, and organization names.

“We see no evidence that the attackers accessed the user database or exfiltrated it,” the message reads. “So we are providing you this information as a matter of transparency and precaution, rather than because we believe that your data was compromised.”

IMPROVEMENTS

Multiple experts interviewed for this story said one persistent problem with DNS-based attacks is that a great deal of organizations tend to take much of their DNS infrastructure for granted. For example, many entities don’t even log their DNS traffic, nor do they keep a close eye on any changes made to their domain records.

Even for those companies making an effort to monitor their DNS infrastructure for suspicious changes, some monitoring services only take snapshots of DNS records passively, or else only do so actively on a once-daily basis. Indeed, Woodcock said PCH relied on no fewer than three monitoring systems, and that none of them alerted his organization to the various one-hour hijacks that hit PCH’s DNS systems.

“We had three different commercial DNS monitoring services, none of which caught it,” he said. “None of them even warned us that it had happened after the fact.”

Woodcock said PCH has since set up a system to poll its own DNS infrastructure multiple times each hour, and to alert immediately on any changes.

Jogbäck said Netnod also has beefed up its monitoring, as well as redoubled efforts to ensure that all of the available options for securing their domain infrastructure were being used. For instance, the company had not previously secured all of its domains with a “domain lock,” a service that requires a registrar to take additional authentication steps before making any modifications to a domain’s records.

“We are really sad we didn’t do a better job of protecting our customers, but we are also a victim in the chain of the attack,” Jogbäck said. “You can change to a better lock after you’ve been robbed, and hopefully make it more difficult for someone to do it again. But I can truly say we have learned a tremendous amount from being a victim in this attack, and we are now much better off than before.”

Woodcock said he’s worried that Internet policymakers and other infrastructure providers aren’t taking threats to the global DNS seriously or urgently enough, and he’s confident the DNSpionage hackers will have plenty of other victims to target and exploit in the months and years ahead.

“All of this is a running battle,” he said. “The Iranians are not just trying to do these attacks to have an immediate effect. They’re trying to get into the Internet infrastructure deeply enough so they can get away with this stuff whenever they want to. They’re looking to get as many ways in as possible that they can use for specific goals in the future.”

RECOMMENDATIONS

John Crain is chief security, stability and resiliency officer at ICANN, the non-profit entity that oversees the global domain name industry. Crain said many of the best practices that can make it more difficult for attackers to hijack a target’s domains or DNS infrastructure have been known for more than a decade.

“A lot of this comes down to data hygiene,” Crain said. “Large organizations down to mom-and-pop entities are not paying attention to some very basic security practices, like multi-factor authentication. These days, if you have a sub-optimal security stance, you’re going to get owned. That’s the reality today. We’re seeing much more sophisticated adversaries now taking actions on the Internet, and if you’re not doing the basic stuff they’re going to hit you.”

Some of those best practices for organizations include:

-Use DNSSEC (both signing zones and validating responses)

-Use registration features like Registry Lock that can help protect domain names records from being changed

-Use access control lists for applications, Internet traffic and monitoring

-Use 2-factor authentication, and require it to be used by all relevant users and subcontractors

-In cases where passwords are used, pick unique passwords and consider password managers

-Review accounts with registrars and other providers

-Monitor certificates by monitoring, for example, Certificate Transparency Logs

from

https://krebsonsecurity.com/2019/02/a-deep-dive-on-the-recent-widespread-dns-hijacking-attacks/

Some 20 of the flaws addressed in February’s update bundle are weaknesses labeled “critical,” meaning Microsoft believes that attackers or malware could exploit them to fully compromise systems through little or no help from users — save from convincing a user to visit a malicious or hacked Web site.

Some 20 of the flaws addressed in February’s update bundle are weaknesses labeled “critical,” meaning Microsoft believes that attackers or malware could exploit them to fully compromise systems through little or no help from users — save from convincing a user to visit a malicious or hacked Web site.