A half dozen technology and security companies — some of them competitors — issued the exact same press release today. This unusual level of cross-industry collaboration caps a successful effort to dismantle ‘WireX,’ an extraordinary new crime machine comprising tens of thousands of hacked Android mobile devices that was used this month to launch a series of massive cyber attacks.

Experts involved in the takedown warn that WireX marks the emergence of a new class of attack tools that are more challenging to defend against and thus require broader industry cooperation to defeat.

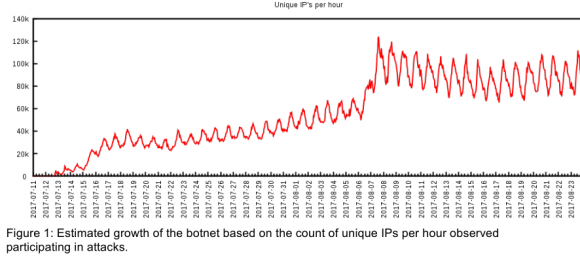

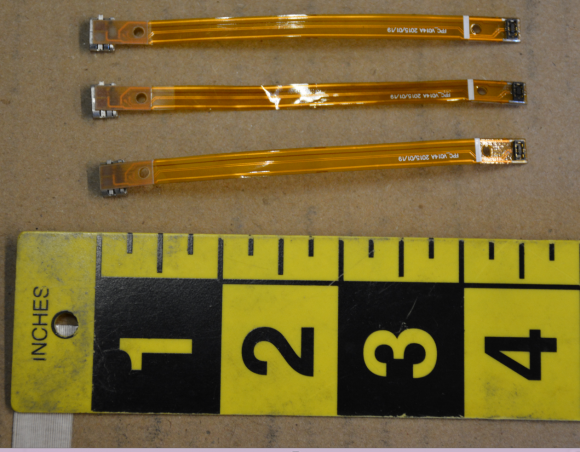

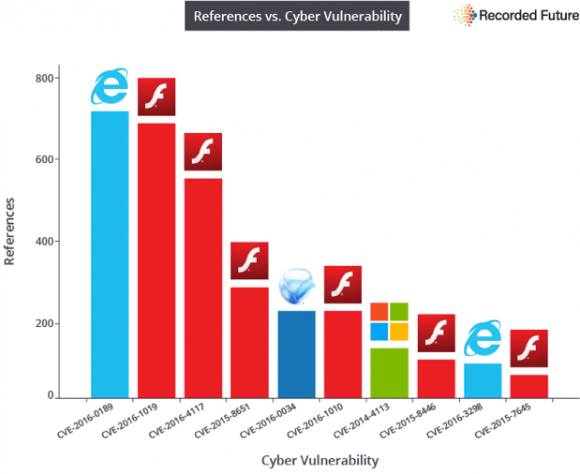

This graphic shows the rapid growth of the WireX botnet in the first three weeks of August 2017.

News of WireX’s emergence first surfaced August 2, 2017, when a modest collection of hacked Android devices was first spotted conducting some fairly small online attacks. Less than two weeks later, however, the number of infected Android devices enslaved by WireX had ballooned to the tens of thousands.

More worrisome was that those in control of the botnet were now wielding it to take down several large websites in the hospitality industry — pelting the targeted sites with so much junk traffic that the sites were no longer able to accommodate legitimate visitors.

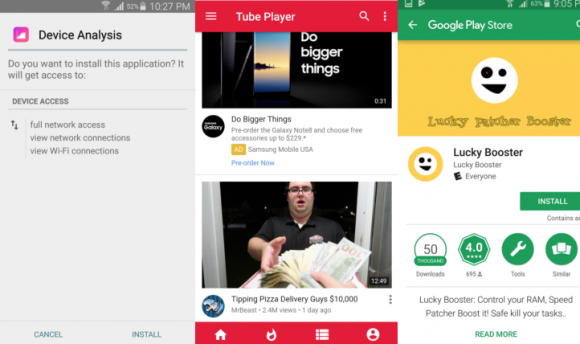

Experts tracking the attacks soon zeroed in on the malware that powers WireX: Approximately 300 different mobile apps scattered across Google‘s Play store that were mimicking seemingly innocuous programs, including video players, ringtones or simple tools such as file managers.

“We identified approximately 300 apps associated with the issue, blocked them from the Play Store, and we’re in the process of removing them from all affected devices,” Google said in a written statement. “The researchers’ findings, combined with our own analysis, have enabled us to better protect Android users, everywhere.”

Perhaps to avoid raising suspicion, the tainted Play store applications all performed their basic stated functions. But those apps also bundled a small program that would launch quietly in the background and cause the infected mobile device to surreptitiously connect to an Internet server used by the malware’s creators to control the entire network of hacked devices. From there, the infected mobile device would await commands from the control server regarding which Websites to attack and how.

A sampling of the apps from Google’s Play store that were tainted with the WireX malware.

Experts involved in the takedown say it’s not clear exactly how many Android devices may have been infected with WireX, in part because only a fraction of the overall infected systems were able to attack a target at any given time. Devices that were powered off would not attack, but those that were turned on with the device’s screen locked could still carry on attacks in the background, they found.

“I know in the cases where we pulled data out of our platform for the people being targeted we saw 130,000 to 160,000 (unique Internet addresses) involved in the attack,” said Chad Seaman, a senior engineer Akamai, a company that specializes in helping firms weather large DDoS attacks (Akamai protected KrebsOnSecurity from hundreds of attacks prior to the large Mirai assault last year).

The identical press release that Akamai and other firms involved in the WireX takedown agreed to publish says the botnet infected a minimum of 70,000 Android systems, but Seaman says that figure is conservative.

“Seventy thousand was a safe bet because this botnet makes it so that if you’re driving down the highway and your phone is busy attacking some website, there’s a chance your device could show up in the attack logs with three or four or even five different Internet addresses,” Seaman said in an interview with KrebsOnSecurity. “We saw attacks coming from infected devices in over 100 countries. It was coming from everywhere.”

BUILDING ON MIRAI

Security experts from Akamai and other companies that participated in the WireX takedown say the basis for their collaboration was forged in the monstrous and unprecedented distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks launched last year by Mirai, a malware strain that seeks out poorly-secured “Internet of things” (IoT) devices such as security cameras, digital video recorders and Internet routers.

The first and largest of the Mirai botnets was used in a giant attack last September that knocked this Web site offline for several days. Just a few days after that — when the source code that powers Mirai was published online for all the world to see and use — dozens of copycat Mirai botnets emerged. Several of those botnets were used to conduct massive DDoS attacks against a variety of targets, leading to widespread Internet outages for many top Internet destinations.

Allison Nixon, director of security research at New York City-based security firm Flashpoint, said the Mirai attacks were a wake-up call for the security industry and a rallying cry for more collaboration.

“When those really large Mirai DDoS botnets started showing up and taking down massive pieces of Internet infrastructure, that caused massive interruptions in service for people that normally don’t deal with DDoS attacks,” Nixon said. “It sparked a lot of collaboration. Different players in the industry started to take notice, and a bunch of us realized that we needed to deal with this thing because if we didn’t it would just keep getting bigger and rampaging around.”

Mirai was notable not only for the unprecedented size of the attacks it could launch but also for its ability to spread rapidly to new infected machines. But for all its sheer firepower, Mirai is not a particularly sophisticated attack platform. Well, not in comparison to WireX, that is.

CLICK-FRAUD ORIGINS

According to the group’s research, the WireX botnet likely began its existence as a distributed method for conducting “click fraud,” a pernicious form of online advertising fraud that will cost publishers and businesses an estimated $16 billion this year, according to recent estimates. Multiple antivirus tools currently detect the WireX malware as a known click fraud malware variant.

The researchers believe that at some point the click-fraud botnet was repurposed to conduct DDoS attacks. While DDoS botnets powered by Android devices are extremely unusual (if not unprecedented at this scale), it is the botnet’s ability to generate what appears regular Internet traffic from mobile browsers that strikes fear in the heart of experts who specialize in defending companies from large-scale DDoS attacks.

DDoS defenders often rely on developing custom “filters” or “signatures” that can help them separate DDoS attack traffic from legitimate Web browser traffic destined for a targeted site. But experts say WireX has the capability to make that process much harder.

That’s because WireX includes its own so-called “headless” Web browser that can do everything a real, user-driven browser can do, except without actually displaying the browser to the user of the infected system.

Also, Wirex can encrypt the attack traffic using SSL — the same technology that typically protects the security of a browser session when an Android user visits a Web site which requires the submission of sensitive data. This adds a layer of obfuscation to the attack traffic, because the defender needs to decrypt incoming data packets before being able to tell whether the traffic inside matches a malicious attack traffic signature.

Translation: It can be far more difficult and time-consuming than usual for defenders to tell WireX traffic apart from clicks generated by legitimate Internet users trying to browse to a targeted site.

“These are pretty miserable and painful attacks to mitigate, and it was these kinds of advanced functionalities that made this threat stick out like a sore thumb,” Akamai’s Seaman said.

NOWHERE TO HIDE

Traditionally, many companies that found themselves on the receiving end of a large DDoS attack sought to conceal this fact from the public — perhaps out of fear that customers or users might conclude the attack succeeded because of some security failure on the part of the victim.

But the stigma associated with being hit with a large DDoS is starting to fade, Flashpoint’s Nixon said, if for no other reason than it is becoming far more difficult for victims to conceal such attacks from public knowledge.

“Many companies, including Flashpoint, have built out different capabilities in order to see when a third party is being DDoS’d,” Nixon said. “Even though I work at a company that doesn’t do DDoS mitigation, we can still get visibility when a third-party is getting attacked. Also, network operators and ISPs have a strong interest in not having their networks abused for DDoS, and many of them have built capabilities to know when their networks are passing DDoS traffic.”

Just as multiple nation states now employ a variety techniques and technologies to keep tabs on nation states that might conduct underground tests of highly destructive nuclear weapons, a great deal more organizations are now actively looking for signs of large-scale DDoS attacks, Seaman added.

“The people operating those satellites and seismograph sensors to detect nuclear [detonations] can tell you how big it was and maybe what kind of bomb it was, but they probably won’t be able to tell you right away who launched it,” he said. “It’s only when we take many of these reports together in the aggregate that we can get a much better sense of what’s really going on. It’s a good example of none of us being as smart as all of us.”

According to the WireX industry consortium, the smartest step that organizations can take when under a DDoS attack is to talk to their security vendor(s) and make it clear that they are open to sharing detailed metrics related to the attack.

“With this information, those of us who are empowered to dismantle these schemes can learn much more about them than would otherwise be possible,” the report notes. “There is no shame in asking for help. Not only is there no shame, but in most cases it is impossible to hide the fact that you are under a DDoS attack. A number of research efforts have the ability to detect the existence of DDoS attacks happening globally against third parties no matter how much those parties want to keep the issue quiet. There are few benefits to being secretive and numerous benefits to being forthcoming.”

Identical copies of the WireX report and Appendix are available at the following links:

Flashpoint

Akamai

Cloudflare

RiskIQ

from

https://krebsonsecurity.com/2017/08/tech-firms-team-up-to-take-down-wirex-android-ddos-botnet/

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) issued an alert Monday urging consumers to be on the lookout for a potential surge in charity scams. The FTC advises those who wish to donate to stick to charities they know, and to be on the lookout for charities or relief Web sites that seem to have sprung up overnight in response to current events (such as houstonfloodrelief.net, registered on Aug. 28, 2017). Sometimes these sites are set up by well-meaning people with the best of intentions (however misguided), but it’s best not to take a chance.