For as long as scam artists have been around so too have opportunistic thieves who specialize in ripping off other scam artists. This is the story about a group of Pakistani Web site designers who apparently have made an impressive living impersonating some of the most popular and well known “carding” markets, or online stores that sell stolen credit cards.

An ad for new stolen cards on Joker’s Stash.

One wildly popular carding site that has been featured in-depth at KrebsOnSecurity — Joker’s Stash — brags that the millions of credit and debit card accounts for sale via their service were stolen from merchants firsthand.

That is, the people running Joker’s Stash say they are hacking merchants and directly selling card data stolen from those merchants. Joker’s Stash has been tied to several recent retail breaches, including those at Saks Fifth Avenue, Lord and Taylor, Bebe Stores, Hilton Hotels, Jason’s Deli, Whole Foods, Chipotle and Sonic. Indeed, with most of these breaches, the first signs that any of the companies were hacked was when their customers’ credit cards started showing up for sale on Joker’s Stash.

Joker’s Stash maintains a presence on several cybercrime forums, and its owners use those forum accounts to remind prospective customers that its Web site — jokerstash[dot]bazar — is the only way in to the marketplace.

The administrators constantly warn buyers to be aware there are many look-alike shops set up to steal logins to the real Joker’s Stash or to make off with any funds deposited with the impostor carding shop as a prerequisite to shopping there.

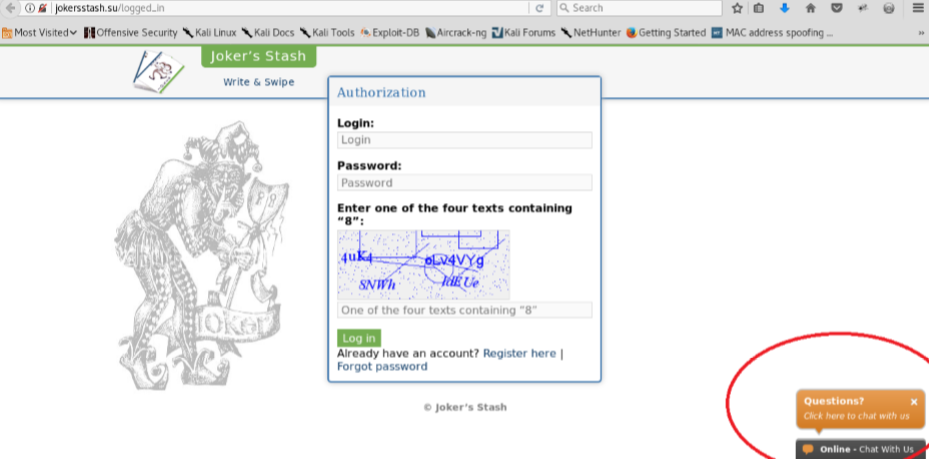

But that didn’t stop a prominent security researcher (not this author) from recently plunking down $100 in bitcoin at a site he thought was run by Joker’s Stash (jokersstash[dot]su). Instead, the proprietors of the impostor site said the minimum deposit for viewing stolen card data on the marketplace had increased to $200 in bitcoin.

The researcher, who asked not to be named, said he obliged with an additional $100 bitcoin deposit, only to find that his username and password to the card shop no longer worked. He’d been conned by scammers scamming scammers.

As it happens, prior to hearing from this researcher I’d received a mountain of research from Jett Chapman, another security researcher who swore he’d unmasked the real-world identity of the people behind the Joker’s Stash carding empire.

Chapman’s research, detailed in a 57-page report shared with KrebsOnSecurity, pivoted off of public information leading from the same jokersstash[dot]su that ripped off my researcher friend.

“I’ve gone to a few cybercrime forums where people who have used jokersstash[dot]su that were confused about who they really were,” Chapman said. “Many of them left feedback saying they’re scammers who will just ask for money to deposit on the site, and then you’ll never hear from them again.”

But the conclusion of Chapman’s report — that somehow jokersstash[dot]su was related to the real criminals running Joker’s Stash — didn’t ring completely accurate, although it was expertly documented and thoroughly researched. So with Chapman’s blessing, I shared his report with both the researcher who’d been scammed and a law enforcement source who’d been tracking Joker’s Stash.

Both confirmed my suspicions: Chapman had unearthed a vast network of sites registered and set up over several years to impersonate some of the biggest and longest-running criminal credit card theft syndicates on the Internet.

THE REAL JOKER’S STASH

The real Joker’s Stash can only be reached after installing a browser extension known as “blockchain DNS.” This component is needed to access any sites ending in the top-level domain names of .bazar,.bit (Namecoin), .coin, .lib and .emc (Emercoin).

Most Web sites use the global Domain Name System (DNS), which serves as a kind of phone book for the Internet by translating human-friendly Web site names (example.com) into numeric Internet address that are easier for computers to manage.

Regular DNS maps Internet addresses to domains by relying on a series of distributed, hierarchical lookups. If one server does not know how to find a domain, that server simply asks another server for the information.

Blockchain-based DNS systems also disseminate that mapping information in a distributed fashion, although via a peer-to-peer method. The entities that operate blockchain-based top level domains (e.g., .bazar) don’t answer to any one central authority — such as the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN), which oversees the global DNS and domain name space. This potentially makes these domains much more difficult for law enforcement agencies to take down.

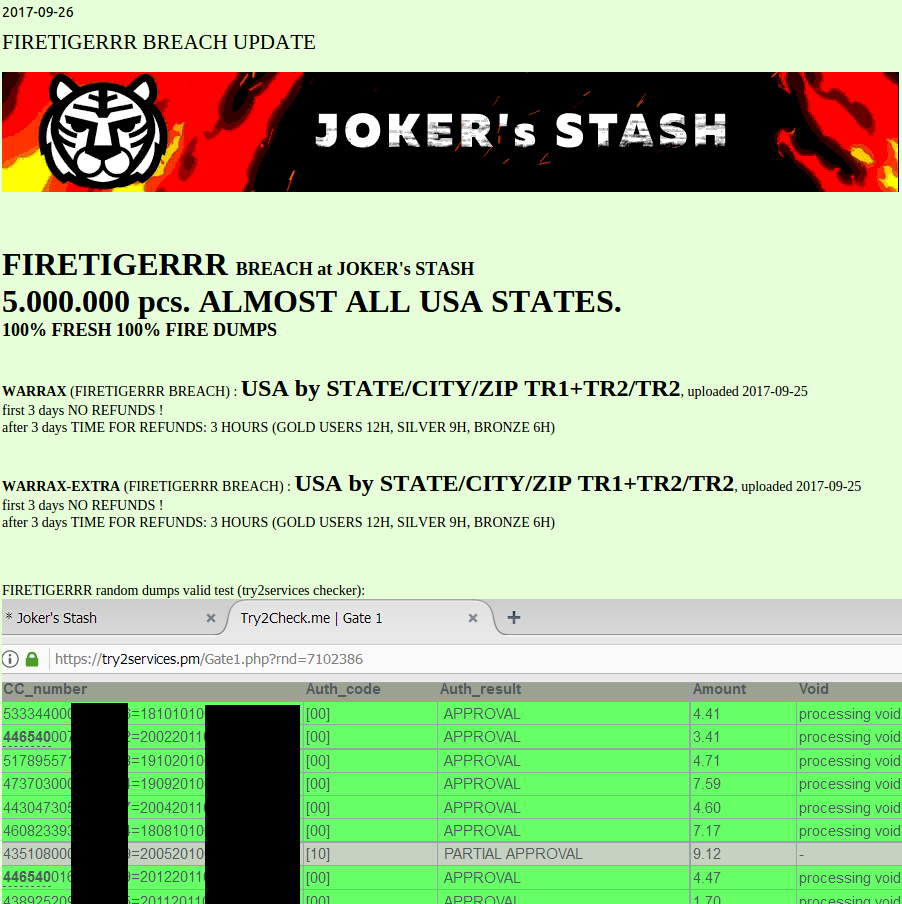

This batch of some five million cards put up for sale Sept. 26, 2017 on the (real) carding site Joker’s Stash has been tied to a breach at Sonic Drive-In

Dark Reading explains further: “When an individual registers a .bit — or another blockchain-based domain — they are able to do so in just a few steps online, and the process costs mere pennies. Domain registration is not associated with an individual’s name or address but with a unique encrypted hash of each user. This essentially creates the same anonymous system as Bitcoin for Internet infrastructure, in which users are only known through their cryptographic identity.”

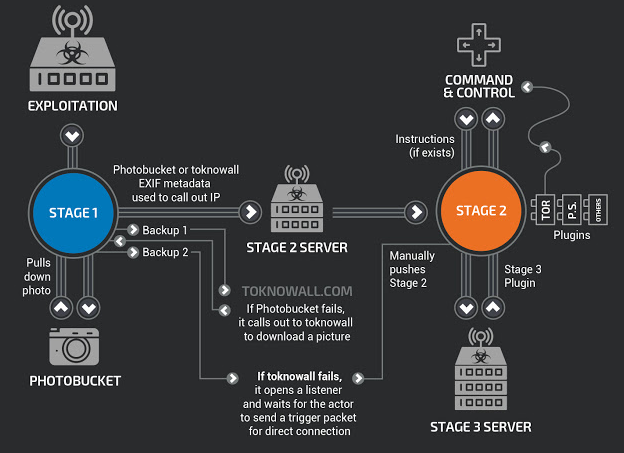

And cybercriminals have taken notice. According to security firm FireEye, over the last year there’s been a surge in the number of threat actors that have started incorporating support for blockchain domains in their malware tools.

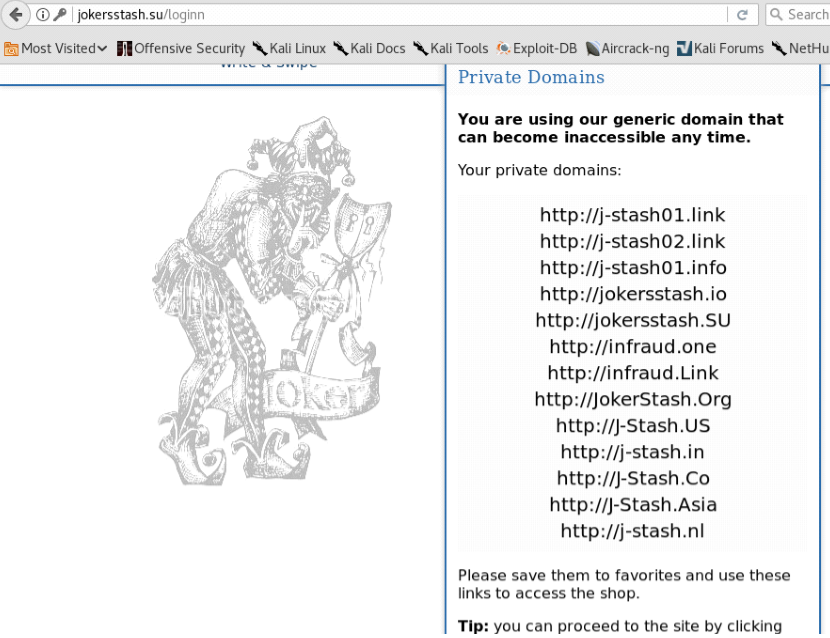

THE FAKE JOKER’S STASH

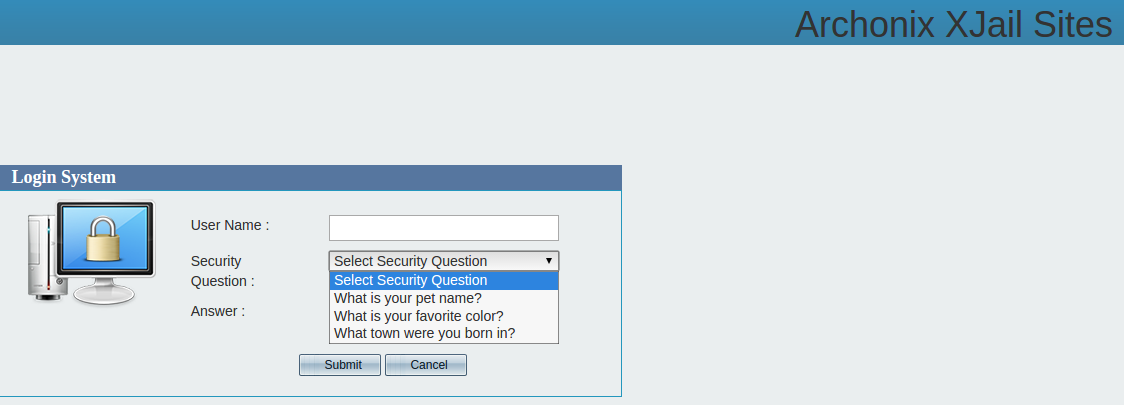

In contrast, the fake version of Joker’s Stash — jokersstash[dot]su — exists on the clear Web and displays a list of “trusted” Joker’s Stash domains that can be used to get on the impostor marketplace. These lists are common on the login pages of carding and other cybercrime sites that tend to lose their domains frequently when Internet do-gooders report them to authorities. The daily reminder helps credit card thieves easily find the new domain should the primary domain get seized by law enforcement or the site’s domain registrar.

Most of the domains in the image above are hosted on the same Internet address: 190.14.38.6 (Offshore Racks S.A. in Panama). But Chapman found that many of these domains map back to just a handful of email addresses, including domain@paysafehost.com, fkaboot@gmail.com, and zanebilly30@gmail.com.Chapman found that adding credit cards to his shopping cart in the fake Joker’s Stash site caused those same cards to show up in his cart when he accessed his account at one of the alternative domains listed in the screenshot above, suggesting that the sites were all connected to the same back-end database.

The email address fkaboot@gmail.com is tied to the name or alias “John Kelly,” as well as 35 domains, according to DomainTools (the full list is here). Most of the sites at those domains borrow names and logos from established credit card fraud sites, including VaultMarket, T12Shop, BriansClub (which uses the head of yours truly on a moving crab to advertise its stolen cards); and the now defunct cybercrime forum Infraud.

Domaintools says the address domain@paysafehost.com also maps to 35 domains, including look-alike domains for major carding sites Bulba, GoldenDumps, ValidShop, McDucks, Mr. Bin, Popeye, and the cybercrime forum Omerta.

The address zanebilly30@gmail.com is connected to 36 domains that feature many of the same impersonated criminal brands as the first two lists.

The domain “paysafehost.com” is not responding at the moment, but until very recently it redirected to a site that tried to scam or phish customers seeking to buy stolen credit card data from VaultMarket. It looks more or less the same as the real VaultMarket’s login page, but Chapman noticed that in the bottom right corner of the screen was a Zendesk chat service soliciting customer questions.

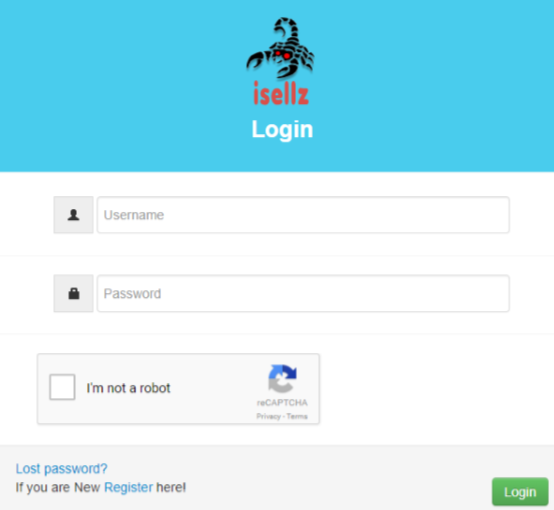

Signing up for an account at paysafehost.com (the fake VaultMarket site) revealed a site that looked like VaultMarket but otherwise massively displayed ads for another carding service — isellz[dot]cc (one of the domains registered to domain@paysafehost.com).

This same Zendesk chat service also was embedded in the homepage of jokersstash[dot]su.

And on isellz[dot]cc:

According to Farsight Security, a company that maps historical connections between Internet addresses and domain names, several other interesting domains used paysafehost[dot]com as their DNS servers, including cvv[dot]kz (CVV stands for the card verification value and it refers to stolen credit card numbers, names and cardholder address that can be used to conduct e-commerce fraud).

All three domains — cvv[dot]kz, and isellz[dot]cc and paysafehost[dot]com list in their Web site registration records the email address xperiasolution@gmail.com, the site xperiasol.com, and the name “Bashir Ahmad.”

XPERIA SOLUTIONS

Searching online for the address xperiasolution@gmail.com turns up a help wanted ad on the Qatar Living Jobs site from October 2017 for a freelance system administrator. The ad was placed by the user “junaidky“, and gives the xperiasolution@gmail.com email address for interested applicants to contact.

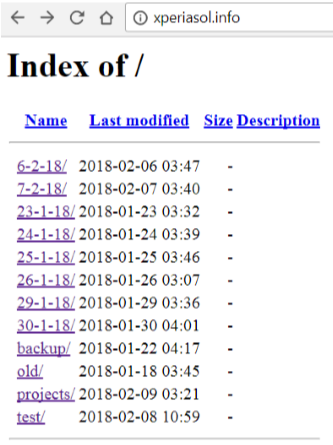

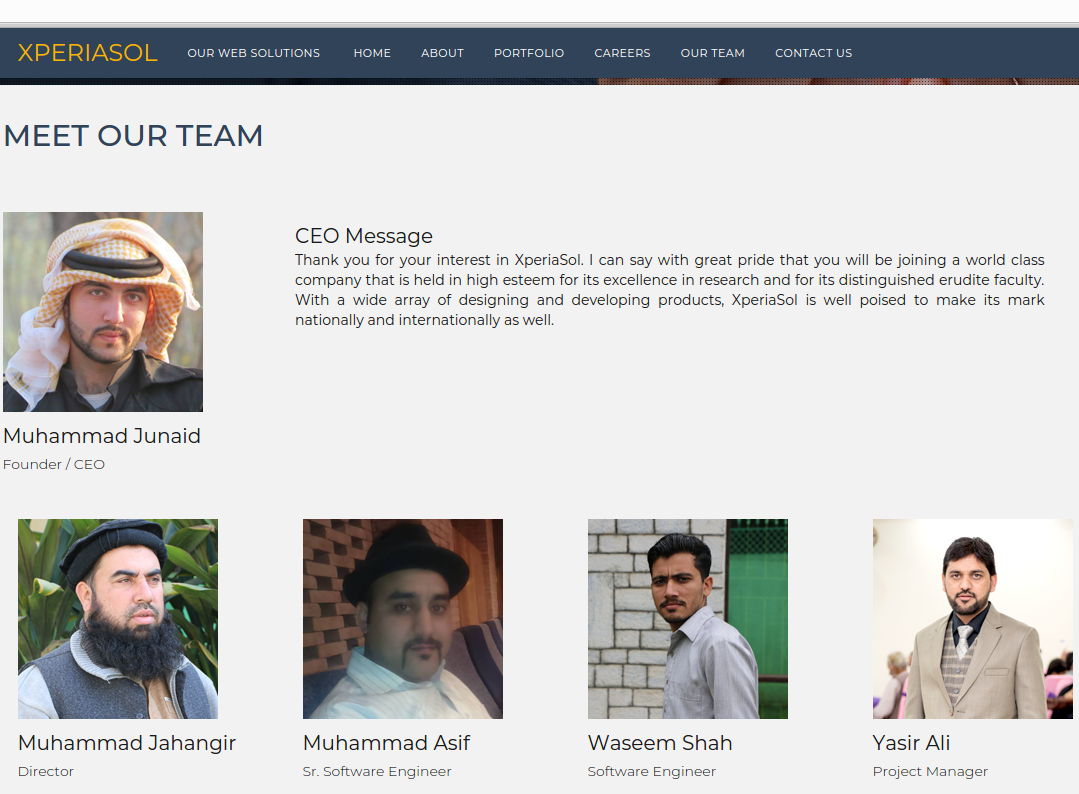

Chapman says at this point in his research he noticed that xperiasolution@gmail.com was also used to register the domain xperiasol.info, which for several years was hosted on the same server as a handful of other sites, such as xperiasol.com — the official Web site Xperia Solution (this site also features a Zen desk chat client in the lower right portion of the homepage).

Xperiasol.com’s Web site says the company is a Web site development firm and domain registrar in Islamabad, Pakistan. The site’s “Meet our Team” page states the founder and CEO of the company is a guy named Muhammad Junaid. Another man pictured as Yasir Ali is the company’s project manager.

We’ll come back to both of these two individuals in a moment. Xperiasol.info also is no longer responding, but not long ago the home page showed several open file directories:

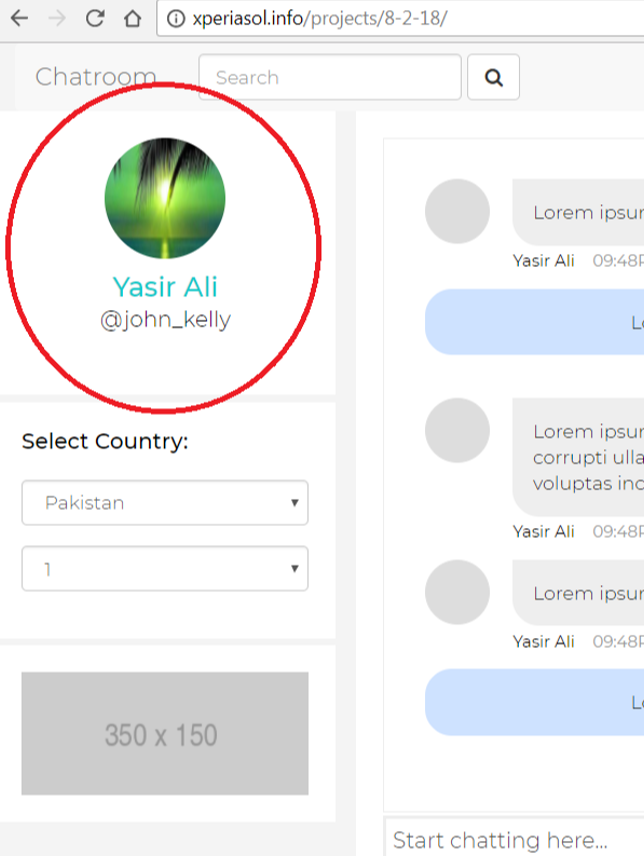

Clicking in the projects directory and drilling down into a project dated Feb. 8, 2018 turns up some kind of chatroom application in development. Recall that dozens of the fake carding domains mentioned above were registered to a “John Kelly” at fkaboot@gmail.com. Have a look at the name next to the chatroom application Web site that was archived at xperiasol.info:

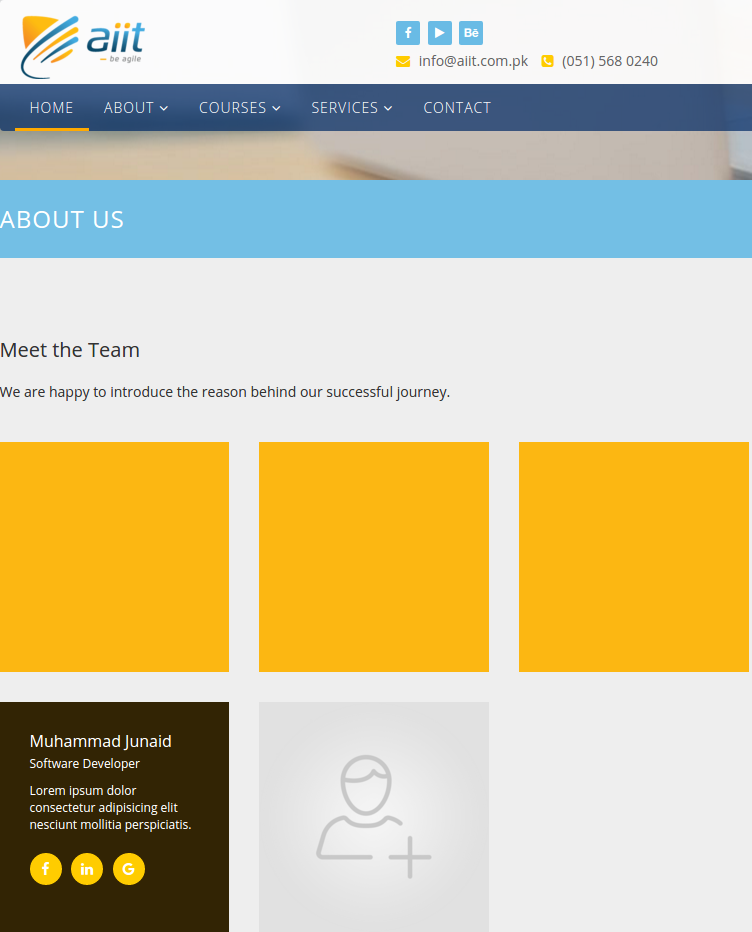

Could Yasir Ali, the project manager of Xperiasol, be the same person who registered so many fake carding domains? What else do we know about Mr. Ali? It appears he runs another business called Agile: Institute of Information Technology. Agile’s domain — aiit.com.pk — was registered to Xperia Sol Technologies in 2016 and hosted on the same server.

Who else that we know besides Mr. Ali is listed on Agile’s “Meet the Team” page? Why Mr. Muhammad Junaid, of course, the CEO and founder of Xperia Sol.

Notice the placeholder “lorem ipsum” content. This can be seen throughout the Web sites for Xperia Sol’s “customers.”

Chapman shared pages of documentation showing that most of the “customers testimonials” supposedly from Xperia Sol’s Web design clients appear to be half-finished sites with plenty of broken links and “lorem ipsum” placeholder content (as is the case with the aiit.com.pk Web site pictured above).

Another “valuable client” listed on Xperia Sol’s home page is Softlottery[dot]com (previously softlogin[dot]com). This site appears to be a business that sells Web site design templates, but it lists its address as Sailor suite room V124, DB 91, Someplace 71745 Earth.

Softlottery/Softlogin features a “corporate business” Web site template that includes a slogan from a major carding forum.

Among the “awesome” corporate design templates that Softlottery has for sale is one loosely based on a motto that has shown up on several carding sites: “We are those, who we are: Verified forum, verified people, serious deals.” Probably the most well-known cybercrime forum using that motto is Omerta (recall from above that the Omerta forum is another brand impersonated by this group).

Flower Land, with the Web address flowerlandllc.com is also listed as a happy Xperia Sol customer and is hosted by Xperia Sol. But most of the links on that site are dead. More importantly, the site’s content appears to have been lifted from the Web site of an actual flower care business in Michigan called myflowerland.com.

Zalmi-TV (zalmi.tv) is supposedly a news media partner of Xperia Sol, but again the Xperia-hosted site is half-finished and full of “lorem ipsum” placeholder content.

THE MASTER MIND?

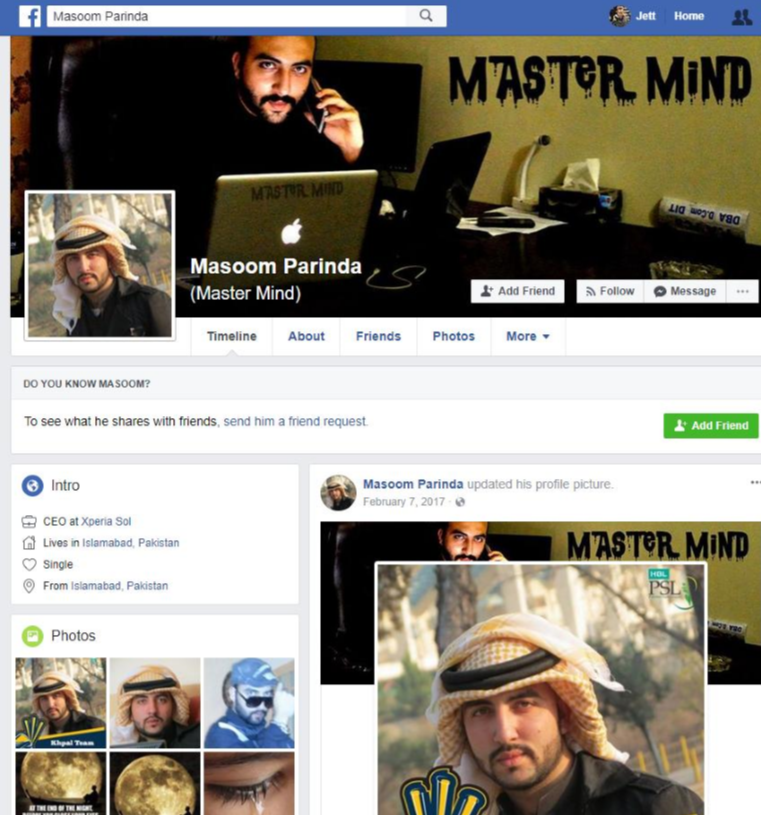

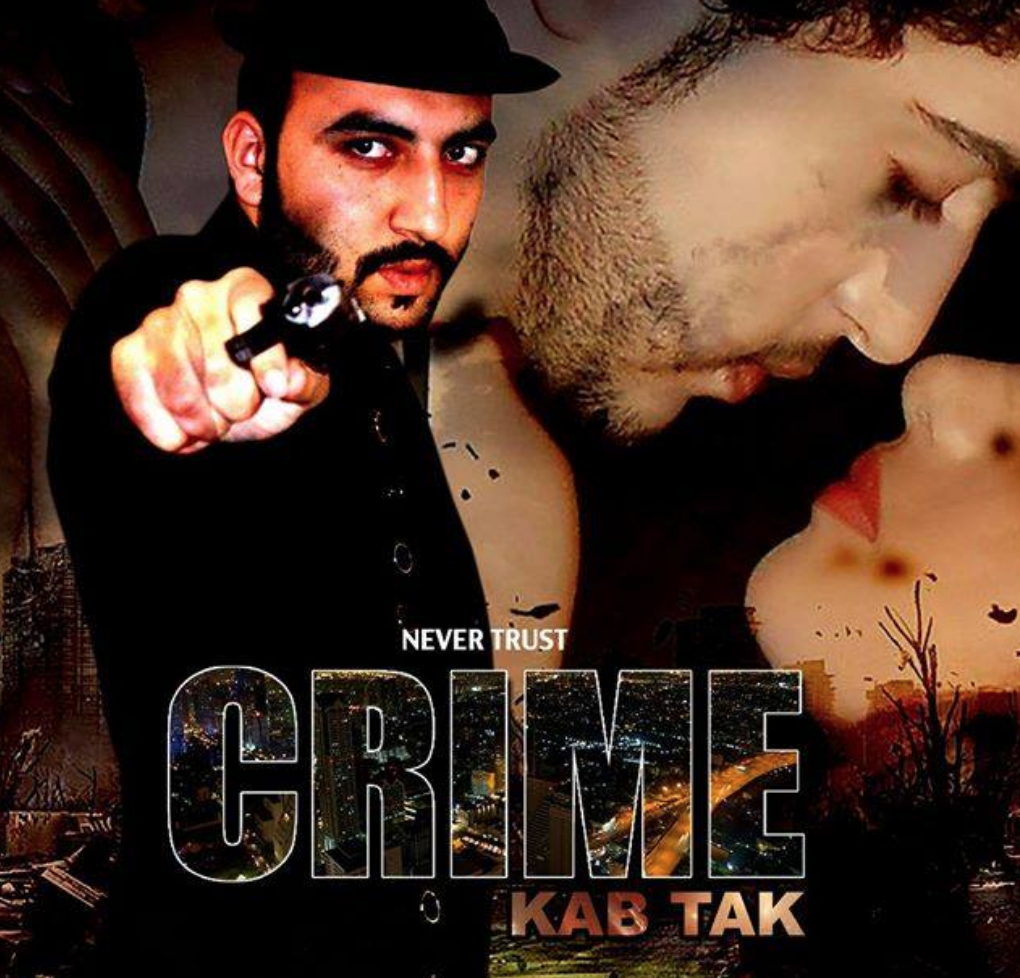

But what about Xperia Sol’s founder, Muhammad Junaid, you ask? Mr. Junaid is known by several aliases, including his stage name, “Masoom Parinda,” a.k.a. “Master Mind). As Chapman unearthed in his research, Junaid has starred in some B-movie action films in Pakistan, and Masoom Parinda is his character’s name.

The fan page for Masoon Parinda, the character played by Muhammad Junaid Ahmed.

Mr. Junaid also goes by the names Junaid Ahmad Khan, and Muhammad Junaid Ahmed. The latter is the one included in a flight itinerary that Junaid posted to his Facebook page in 2014.

There are also some interesting photos of his various cars — all of which have the Masoom Parinda nickname “Master Mind” written on the back window. There is also something else on each car’s rear window: A picture of a black and red scorpion.

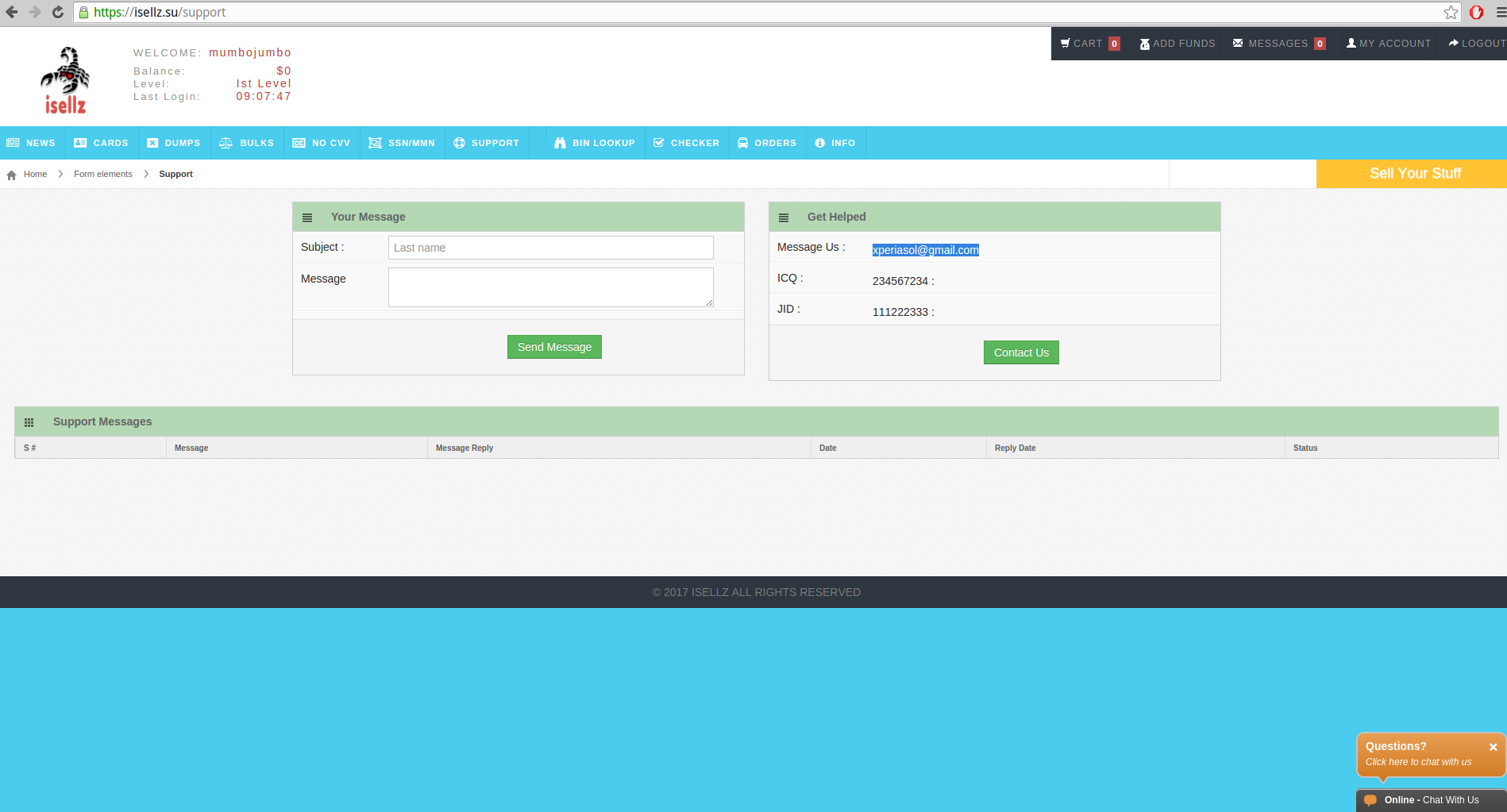

Recall the logo that was used at the top of isellz[dot]cc, the main credit card fraud site tied to xperiasolutions@gmail.com. It features a giant black and red scorpion:

The isellz Web site features a scorpion as a logo.

I reached out to Mr. Junaid/Khan via his Facebook page. Soon after that, his Facebook profile disappeared. But not before KrebsOnSecurity managed to get a copy of the page going back several years. Mr. Junaid/Khan is apparently friends with a local man named Bashar Ahmad. Recall that a “Bashar Ahmad” was the name tied to the domain registrations — cvv[dot]kz, and isellz[dot]cc and paysafehost[dot]com — and to the email address xperiasolution@gmail.com.

Mr. Ahmed also has a Facebook page going back more than seven years. In one of those posts, he publishes a picture of a scorpion very similar to the one on isellz[dot]cc and on Mr. Khan’s automobiles.

A screen shot from Bashir Ahmad’s Facebook postings.

At the conclusion of his research, Chapman said he discovered one final and jarring connection between Xperia Sol and the carding site isellz[dot]cc: When isellz customers have trouble using the site, they can submit a support ticket. Where does that support ticket go? Would you believe to xperiasol@gmail.com? Click the image below to enlarge.

It could be that all of this evidence pointing back to Xperia Sol is just a coincidence, or an elaborate character assassination scheme cooked up by one of the company’s competitors. Or perhaps Mr. Junaind/Khan is simply researching a new role as a hacker in an upcoming Pakistani cinematic thriller:

Mr. Junaid/Khan, in an online promotion for a movie he stars in about crime.

In many ways, creating a network of fake carding sites is the perfect cybercrime. After all, nobody is going to call the cops on people who make a living ripping off cybercriminals. Nor will anyone help the poor sucker who gets snookered by one of these fake carding sites. Caveat Emptor!

from

https://krebsonsecurity.com/2018/05/will-the-real-jokers-stash-come-forward/

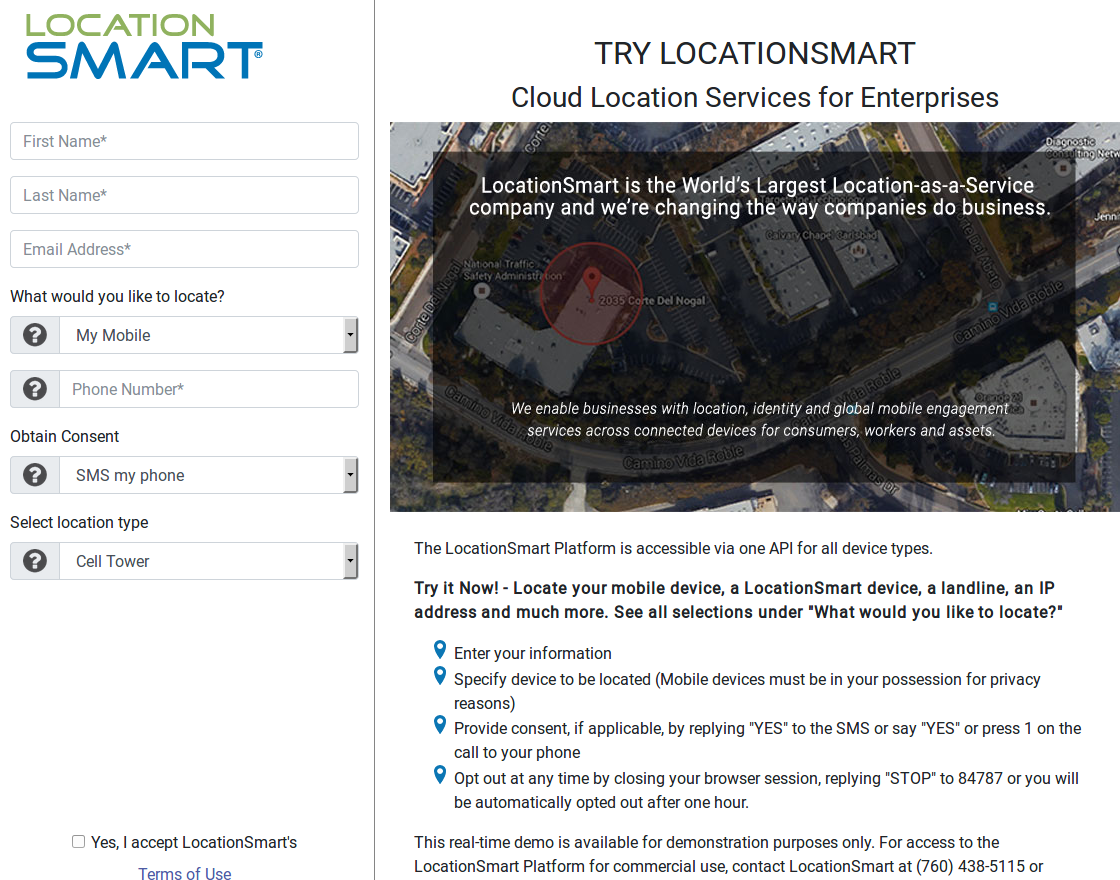

It may be tough to put a price on one’s location privacy, but here’s something of which you can be sure: The mobile carriers are selling data about where you are at any time, without your consent, to third-parties for probably far less than you might be willing to pay to secure it.

It may be tough to put a price on one’s location privacy, but here’s something of which you can be sure: The mobile carriers are selling data about where you are at any time, without your consent, to third-parties for probably far less than you might be willing to pay to secure it.