Identity thieves have perfected a scam in which they impersonate existing customers at retail mobile phone stores, pay a small cash deposit on pricey new phones, and then charge the rest to the victim’s account. In most cases, switching on the new phones causes the victim account owner’s phone(s) to go dead. This is the story of a Pennsylvania man who allegedly died of a heart attack because his wife’s phone was switched off by ID thieves and she was temporarily unable to call for help.

Little did MaryLou know, but identity thieves had the day before entered a “premium authorized Verizon dealer” store in Florida and impersonated the Schwartzes. The thieves paid a $150 cash deposit to “upgrade” the elderly couple’s simple mobiles to new iPhone 6s devices, with the balance to be placed on the Schwartz’s account.

“Despite her severely disabled and elderly condition, MaryLou Schwartz was finally able to retrieve her husband’s cellular telephone using a mechanical arm,” reads a lawsuit (PDF) filed in Beaver County, Penn. on behalf of the Schwartz’s two daughters, alleging negligence by the Florida mobile phone store. “This monumental, determined and desperate endeavor to reach her husband’s working telephone took Mrs. Schwartz approximately forty minutes to achieve due to her condition. This vital delay in reaching emergency help proved to be fatal.”

By the time paramedics arrived, Mr. Schwartz was pronounced dead. MaryLou Schwartz died seventeen days later, on March 8, 2016. Incredibly, identity thieves would continue robbing the Schwartzes even after they were both deceased: According to the lawsuit, on April 14, 2016 the account of MaryLou Schwartz was again compromised and a tablet device was also fraudulently acquired in MaryLou’s name.

The Schwartz’s daughters say they didn’t learn about the fraud until after both parents passed away. According to them, they heard about it from the guy at a local Verizon reseller that noticed his longtime customers’ phones had been deactivated. That’s when they discovered that while their mother’s phone was inactive at the time of her father’s death, their father’s mobile had inexplicably been able to make but not receive phone calls.

KNOW YOUR RIGHTS AND OPTIONS

Exactly what sort of identification was demanded of the thieves who impersonated the Schwartzes is in dispute at the moment. But it seems clear that this is a fairly successful and common scheme for thieves to steal (and, in all likelihood, resell) high-end phones.

Lorrie Cranor, chief technologist for the U.S. Federal Trade Commission, was similarly victimized this summer when someone walked into a mobile phone store, claimed to be her, asked to upgrade her phones and walked out with two brand new iPhones assigned to her telephone numbers.

“My phones immediately stopped receiving calls, and I was left with a large bill and the anxiety and fear of financial injury that spring from identity theft,” Cranor wrote in a blog on the FTC’s site. Cranor’s post is worth a read, as she uses the opportunity to explain how she recovered from the identity theft episode.

She also used her rights under the Fair Credit Reporting Act, which requires that companies provide business records related to identity theft to victims within 30 days of receiving a written request. Cranor said the mobile store took about twice that time to reply, but ultimately explained that the thief had used a fake ID with Cranor’s name but the impostor’s photo.

“She had acquired the iPhones at a retail store in Ohio, hundreds of miles from where I live, and charged them to my account on an installment plan,” Cranor wrote. “It appears she did not actually make use of either phone, suggesting her intention was to sell them for a quick profit. As far as I’m aware the thief has not been caught and could be targeting others with this crime.”

Cranor notes that records of identity thefts reported to the FTC provide some insight into how often thieves hijack a mobile phone account or open a new mobile phone account in a victim’s name.

“In January 2013, there were 1,038 incidents of these types of identity theft reported, representing 3.2% of all identity theft incidents reported to the FTC that month,” she explained. “By January 2016, that number had increased to 2,658 such incidents, representing 6.3% of all identity thefts reported to the FTC that month. Such thefts involved all four of the major mobile carriers.”

The reality, Cranor said, is that identity theft reports to the FTC likely represent only the tip of a much larger iceberg. According to data from the Identity Theft Supplement to the 2014 National Crime Victimization Survey conducted by the U.S. Department of Justice, less than 1% of identity theft victims reported the theft to the FTC.

While dealing with diverted calls can be a hassle, having your phone calls and incoming text messages siphoned to another phone also can present new security problems, thanks to the growing use of text messages in authentication schemes for financial services and other accounts.

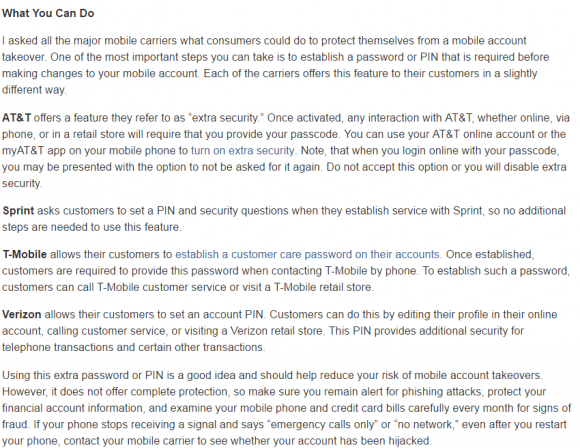

Perhaps the most helpful part of Cranor’s post is a section on the security options offered by the four major mobile providers in the U.S. For example, AT&T offers an “extra security” feature that requires customers to present a custom passcode when dealing with the wireless provider via phone or online.

“All of the carriers have slightly different procedures but seem to suffer from the same problem, which is that they’re relying on retail stores relying on store employee look at drivers license,” Cranor told KrebsOnSecurity. “They don’t use services that will check the information on the drivers license, and so that [falls to] the store employee who has no training in spotting fake IDs.”

Some of the security options offered by the four major providers. Source: FTC.

It’s important to note that secret passcodes often can be bypassed by determined attackers or identity thieves who are adept at social engineering — that is, tricking people into helping them commit fraud.

I’ve used a six-digit passcode for more than two years on my account with AT&T, and last summer noticed that I’d stopped receiving voicemails. A call to AT&T’s customer service revealed that all voicemails were being forwarded to a number in Seattle that I did not recognized or authorize.

Since it’s unlikely that the attackers in this case guessed my six-digit PIN, they likely tricked a customer service representative at AT&T into “authenticating” me via other methods — probably by offering static data points about me such as my Social Security number, date of birth, and other information that is widely available for sale in the cybercrime underground on virtually all Americans over the age of 35. In any case, Cranor’s post has inspired me to exercise my rights under the FCRA and find out for certain.

Vineetha Paruchuri, a masters in computer science student at Dartmouth College, recently gave a talk at the Bsides security conference in Las Vegas on her research into security at the major U.S. mobile phone providers. Paruchuri said all of the major mobile providers suffer from a lack of strict protocols for authenticating customers, leaving customer service personnel exposed to social engineering.

“As a computer science student, my contention was that if we take away the control from the humans, we can actually make this process more secure,” Paruchuri said.

Paruchuri said perhaps the most dangerous threat is the smooth-talking social engineer who spends time collecting information about the verbal shorthand or mobile industry patois used by employees at these companies. The thief then simply phones up customer support and poses as a mobile store technician or employee trying to assist a customer. This was the exact approach used in 2014, when young hooligans tricked my then-ISP Cox Communications into resetting the password for my Cox email account.

I suppose one aspect of this problem that makes the lack of strong customer authentication measures by the mobile industry so frustrating is that it’s hard to imagine a device which holds more personal and intimate details about you than your wireless phone. After all, your phone likely knows where you were last night, when you last traveled, the phone number you last called and numbers you most frequently text.

And yet, the best the mobile providers and their fleet of reseller stores can do to tell you apart from an ID thief is to store a PIN that could be bypassed by clever social engineers (who may or may not be shaving yet).

A NOTE FOR AT&T READERS

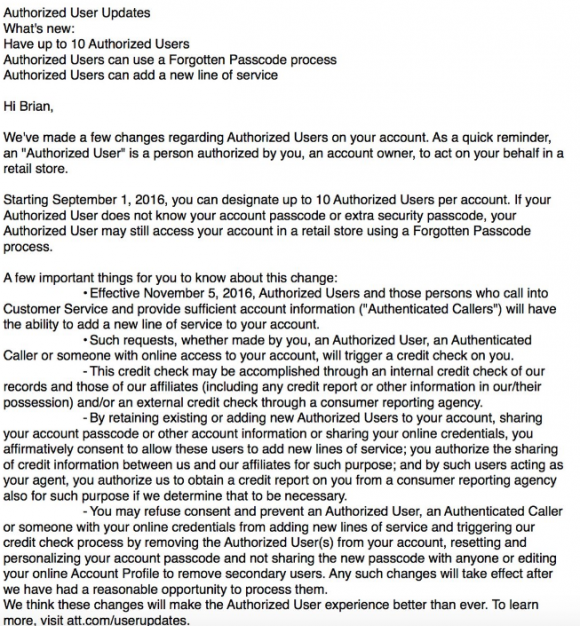

By the way, readers with AT&T phones may have received a notice this week that AT&T is making some changes to “authorized users” allowed on accounts. The notice advised that starting Sept. 1, 2016, customers can designate up to 10 authorized users per account.

“If your Authorized User does not know your account passcode or extra security passcode, your Authorized User may still access your account in a retail store using a Forgotten Passcode process. Effective Nov. 5, 2016, Authorized Users and those persons who call into Customer Service and provide sufficient account information (“Authenticated Callers” Will have the ability to add a new line of service to your account. Such requests, whether made by you, an Authorized User, an Authenticated Caller or someone with online access to your account, will trigger a credit check on you.”

AT&T’s message this week about upcoming account changes.

I asked AT&T about what need this new policy was designed to address, and the company responded that AT&T has made no changes to how an authorized user can be added to an account. AT&T spokesman Jim Greer sent me the following:

“With this notice, we are simply increasing the number of authorized users you may add to your account and giving them the ability to add a line in stores or over the phone. We made this change since more customers have multiple lines for multiple people. Authorized users still cannot access the account holder’s sensitive personal information.”

“Over the past several years, the authentication process has been strengthened. In stores, we’re safeguarding customers through driver’s license or other government issued ID authentication. We use a two-factor authentication when you contact us online or by phone that requires a one-time PIN. We’re continuing our efforts to better protect customers, with additional improvements on the horizon.”

“You don’t have to designate anyone to become an authorized user on your account. You will be notified if any significant changes are made to your account by an authorized user, and you can remove any person as an authorized user at any time.”

The rub is what AT&T does — or more specifically, what the AT&T customer representative does — to verify your identity when the caller says he doesn’t remember his PIN or passcode. If they allow PIN-less authentication by asking for your Social Security number, date of birth and other static information about you, ID thieves can defeat that easily.

Has someone fraudulently ordered phone service or phones in your name? Sound off in the comments below.

If you’re wondering what you can do to shield yourself and your family against identity theft, check out these primers:

How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Embrace the Security Freeze (this primer goes well beyond security freezes and includes a detailed Q&A as well as other tips to help prevent and recover from ID theft).

Are Credit Monitoring Services Worth It?

The Lowdown on Freezing Your Kid’s Credit

from

http://redirect.viglink.com?u=http%3A%2F%2Fkrebsonsecurity.com%2F2016%2F08%2Fa-life-or-death-case-of-identity-theft%2F&key=ddaed8f51db7bb1330a6f6de768a69b8

No comments:

Post a Comment