It’s been just over a year since the world witnessed some of the world’s top online Web sites being taken down for much of the day by “Mirai,” a zombie malware strain that enslaved “Internet of Things” (IoT) devices such as wireless routers, security cameras and digital video recorders for use in large-scale online attacks.

Now, experts are sounding the alarm about the emergence of what appears to be a far more powerful strain of IoT attack malware — variously named “Reaper” and “IoTroop” — that spreads via security holes in IoT software and hardware. And there are indications that over a million organizations may be affected already.

Reaper isn’t attacking anyone yet. For the moment it is apparently content to gather gloom to itself from the darkest reaches of the Internet. But if history is any teacher, we are likely enjoying a period of false calm before another humbling IoT attack wave breaks.

On Oct. 19, 2017, researchers from Israeli security firm CheckPoint announced they’ve been tracking the development of a massive new IoT botnet “forming to create a cyber-storm that could take down the Internet.” CheckPoint said the malware, which it called “IoTroop,” had already infected an estimated one million organizations.

The discovery came almost a year to the day after the Internet witnessed one of the most impactful cyberattacks ever — against online infrastructure firm Dyn at the hands of “Mirai,” an IoT malware strain that first surfaced in the summer of 2016. According to CheckPoint, however, this new IoT malware strain is “evolving and recruiting IoT devices at a far greater pace and with more potential damage than the Mirai botnet of 2016.”

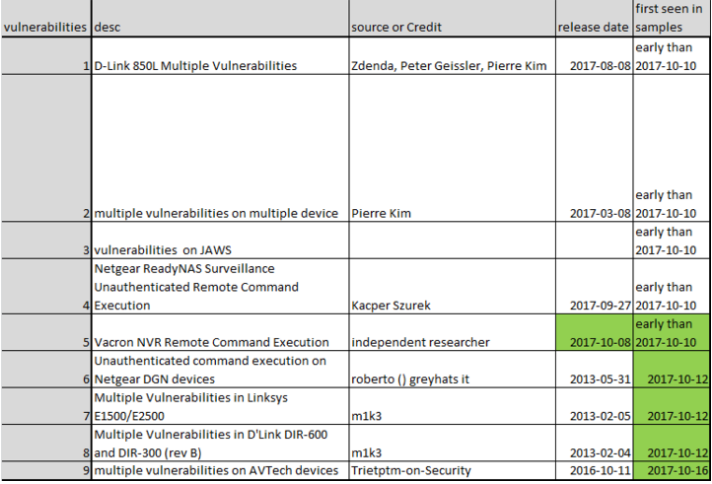

Unlike Mirai — which wriggles into vulnerable IoT devices using factory-default or hard-coded usernames and passwords — this newest IoT threat leverages at least nine known security vulnerabilities across nearly a dozen different device makers, including AVTECH, D-Link, GoAhead, Netgear, and Linksys, among others (click each vendor’s link to view security advisories for the flaws).

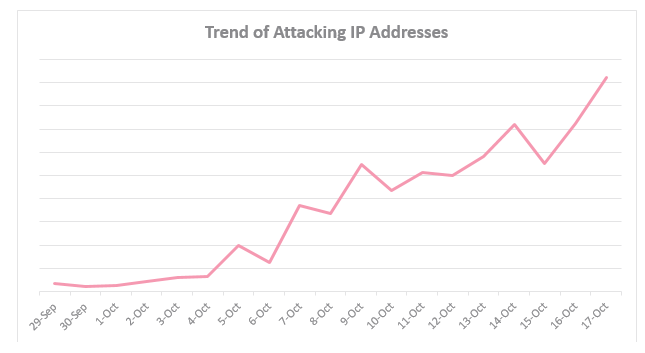

This graphic from CheckPoint charts a steep, recent rise in the number of Internet addresses trying to spread the new IoT malware variant, which CheckPoint calls “IoTroop.”

Both Mirai and IoTroop are computer worms; they are built to spread automatically from one infected device to another. Researchers can’t say for certain what IoTroop will be used for but it is based at least in part on Mirai, which was made to launch distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks.

While DDoS attacks target a single Web site or Internet host, they often result in widespread collateral Internet disruption. IoT malware spreads by scanning the Internet for other vulnerable devices, and sometimes this scanning activity is so aggressive that it constitutes an unintended DDoS on the very home routers, Web cameras and DVRs that the bot code is trying to subvert and recruit into the botnet.

However, according to research released Oct. 20 by Chinese security firm Netlab 360, the scanning performed by the new IoT malware strain (Netlab calls it the more memorable “Reaper”) is not very aggressive, and is intended to spread much more deliberately than Mirai. Netlab’s researchers say Reaper partially borrows some Mirai source code, but is significantly different from Mirai in several key behaviors, including an evolution that allows Reaper to more stealthily enlist new recruits and more easily fly under the radar of security tools looking for suspicious activity on the local network.

WARNING SIGNS, AND AN EVOLUTION

Few knew or realized it at the time, but even before the Mirai attacks commenced in August 2016 there were ample warning signs that something big was brewing. Much like the seawater sometimes recedes hundreds of feet from its normal coastline just before a deadly tsunami rushes ashore, cybercriminals spent the summer of 2016 using their state-of-the-art and new Mirai malware to siphon control over poorly-secured IoT devices from other hackers who were using inferior IoT malware strains.

Mirai was designed to wrest control over systems infected with variants of an early IoT malware contagion known as “Qbot” — and it did so with gusto immediately following its injection into the Internet in late July 2016. As documented in great detail in “Who Is Anna Senpai, the Mirai Worm Author?“, the apparent authors of Mirai taunted the many Qbot botmasters in hacker forum postings, promising they had just unleashed a new digital disease that would replace all Qbot infected devices with Mirai.

Mirai’s architects were true to their word: their creation mercilessly seized control over hundreds of thousands of IoT devices, spreading the disease globally and causing total extinction of Qbot variants. Mirai had evolved, and Qbot went the way of the dinosaurs.

On Sept. 20, 2016, KrebsOnSecurity.com was hit with a monster denial-of-service attack from the botnet powered by the first known copy of Mirai. That attack, which clocked in at 620 Gbps, was almost twice the size that my DDoS mitigation firm at the time Akamai had ever mitigated before. They’d been providing my site free protection for years, but when the Mirai attackers didn’t go away and turned up the heat, Akamai said the attack on this site was causing troubles for its paying customers, and it was time to go.

Thankfully, several days later Google brought KrebsOnSecurity into the stable of journalist and activist Web sites that qualify for its Project Shield program, which offers DDoS protection to newsrooms and Web sites facing various forms of online censorship.

The same original Mirai botnet would be used to launch a huge attack — over one terabit of data per second — against French hosting firm OVH. After the media attention paid to this site’s attack and the OVH assault, the Mirai authors released the source code for their creation, spawning dozens of copycat Mirai clones that all competed for the right to infest a finite pool of vulnerable IoT devices.

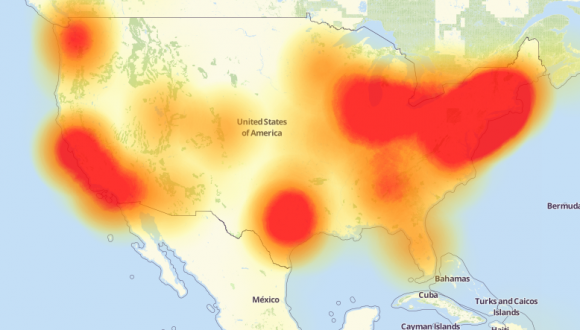

Probably the largest Mirai clone to rise out of the source code spill was used in a highly disruptive attack on Oct. 20, 2016 against Internet infrastructure giant Dyn (now part of Oracle). Some of the Internet’s biggest destinations — including Twitter, SoundCloud, Spotify and Reddit — were unreachable for large chunks of time that day because Mirai targeted a critical service that Dyn provides these companies.

A depiction of the outages caused by the Mirai attacks on Dyn, an Internet infrastructure company. Source: Downdetector.com.

[AUTHOR’S NOTE: Some people believe that the Dyn attack was in retribution for information presented publicly hours before the attack by Dyn researcher Doug Madory. The talk was about research we had worked on together for a story exploring the rather sketchy history of a DDoS mitigation firm that had a talent for annexing Internet address space from its neighbors in a personal grudge match between that mitigation firm and the original Mirai authors and botmasters.]

It’s a safe bet that whoever is responsible for building this new Reaper IoT botnet will have more than enough firepower capable of executing Dyn-like attacks at Internet pressure points. Attacks like these can cause widespread Internet disruption because they target virtual gateways where third-party infrastructure providers communicate with hordes of customer Web sites, which in turn feed the online habits of countless Internet users.

It’s critical to observe that Reaper may not have been built for launching DDoS attacks: A global network of millions of hacked IoT devices can be used for a variety of purposes — such as serving as a sort of distributed proxy or anonymity network — or building a pool of infected devices that can serve as jumping-off points for exploring and exploiting other devices within compromised corporate networks.

“While some technical aspects lead us to suspect a possible connection to the Mirai botnet, this is an entirely new campaign rapidly spreading throughout the globe,” CheckPoint warns. “It is too early to assess the intentions of the threat actors behind it, but it is vital to have the proper preparations and defense mechanisms in place before an attack strikes.”

AND THE GOOD NEWS IS?

There have been positive developments on the IoT security front: Two possible authors of Mirai have been identified (if not yet charged), and some of Mirai’s biggest botmasters have been arrested and sentenced.

Some of the most deadly DDoS attack-for-hire services on the Internet were either run out of business by Mirai or have been forcibly shuttered in the past year, including vDOS — one of the Internet’s longest-running attack services. The alleged providers of vDOS — two Israeli men first outed by KrebsOnSecurity after their service was massively hacked last year — were later arrested and are currently awaiting trial in Israeli for related cybercrime charges.

Using a combination of arrests and interviews, the FBI and its counterparts in Europe have made it clear that patronizing or selling DDoS-for-hire services — often known as “booters” or “stressers” — is illegal activity that can land violators in jail.

The front page of vDOS, when it was still online last year. vDOS was powered by an IoT botnet similar to Mirai and Reaper.

Public awareness of IoT security is on the rise, with lawmakers in Washington promising legislative action if the tech industry continues to churn out junky IoT hardware that is the Internet-equivalent of toxic waste.

Nevertheless, IoT device makers continue to ship products with either little to no security turned on by default or with ill-advised features which can be used to subvert any built-in security.

WHAT YOU CAN DO

According to Netlab, about half of the security vulnerabilities exploited by Reaper were first detailed in just the past few months, suggesting there may be a great number of unpatched and vulnerable systems in real danger from this new IoT malware strain.

Check to make sure your network isn’t part of the problem: Netlab’s advisory links to specific patches available by vendor, as well as indicators of compromise and the location of various Reaper control networks. CheckPoint’s post breaks down affected devices by version number but doesn’t appear to include links to security advisories or patches.

Please note that many of the affected devices are cameras or DVRs, but there also are quite a few consumer wired/wireless routers listed here (particularly for D-Link and Linksys devices).

One incessant problem with popular IoT devices is the inclusion of peer-to-peer (P2P) networking capability inside countless security cameras, DVRs and other gear. Jake Reynolds, a partner and consultant at Kansas City, Mo.-based Depth Security, published earlier this month research on a serious P2P weakness built into many FLIR/Lorex DVRs and security cameras that could let attackers remotely locate and gain access to vulnerable systems that otherwise are not directly connected to the Internet (FLIR’s updated advisory and patches are here).

In Feb. 2016, KrebsOnSecurity warned about a similar weakness powering the P2P component embedded in countless security cameras made by Foscam. That story noted that while the P2P component was turned on by default, disabling it in the security settings of the device did nothing to actually turn off P2P communications. Being able to do that was only possible after applying a firmware patch Foscam made available after users started complaining. My advice is to stay away from products that advertise P2P functionality.

Another reason IoT devices are ripe for exploitation by worms like Reaper and Mirai is that vendors infrequently release security updates for their firmware, and when they do there’s often no easy method available to notify users. Also, these updates are notoriously hard to do and easy to screw up, often leaving the unwary and unlearned with an oversized paperweight after a botched firmware update. So if it’s time to update your device, do it slowly and carefully.

What’s interesting about Reaper is that it is currently built to live harmoniously with Mirai. It’s not immediately clear whether the two IoT malware strains compete for any of the same devices, although some overlaps are bound to occur — particularly as the Reaper authors add new functionality and spreading mechanisms (both Netlab and Checkpoint say the Reaper code appears to be a work-in-progress).

That new Reaper functionality could well include the ability to seek out and supplant Mirai infections (much like Mirai did with Qbot), which would help Reaper to grow to even more terrifying numbers.

No matter what innovation Reaper brings, I’m hopeful that the knowledge being shared within the security community about how to defend against the Mirai attacks today will prove useful in ultimately helping to blunt any attacks from Reaper tomorrow. <Fingers crossed>

Speaking of calms before storms, KrebsOnSecurity.com soon will get its first major facelift since its inception in Dec. 2009. The changes are more structural than cosmetic; we’re striving to make the site more friendly to mobile devices, while maintaining the simple, almost minimalist look and feel of this site. I’ll make another announcement as we get closer to the switch (just so everyone doesn’t freak out and report the site’s been hacked).

from

https://krebsonsecurity.com/2017/10/reaper-calm-before-the-iot-security-storm/

No comments:

Post a Comment